Aizu – Where Resilience and Love of Home Prevails. Video

Mountainwatch | Words Micah Evangelista. Photos Dylan Hallet

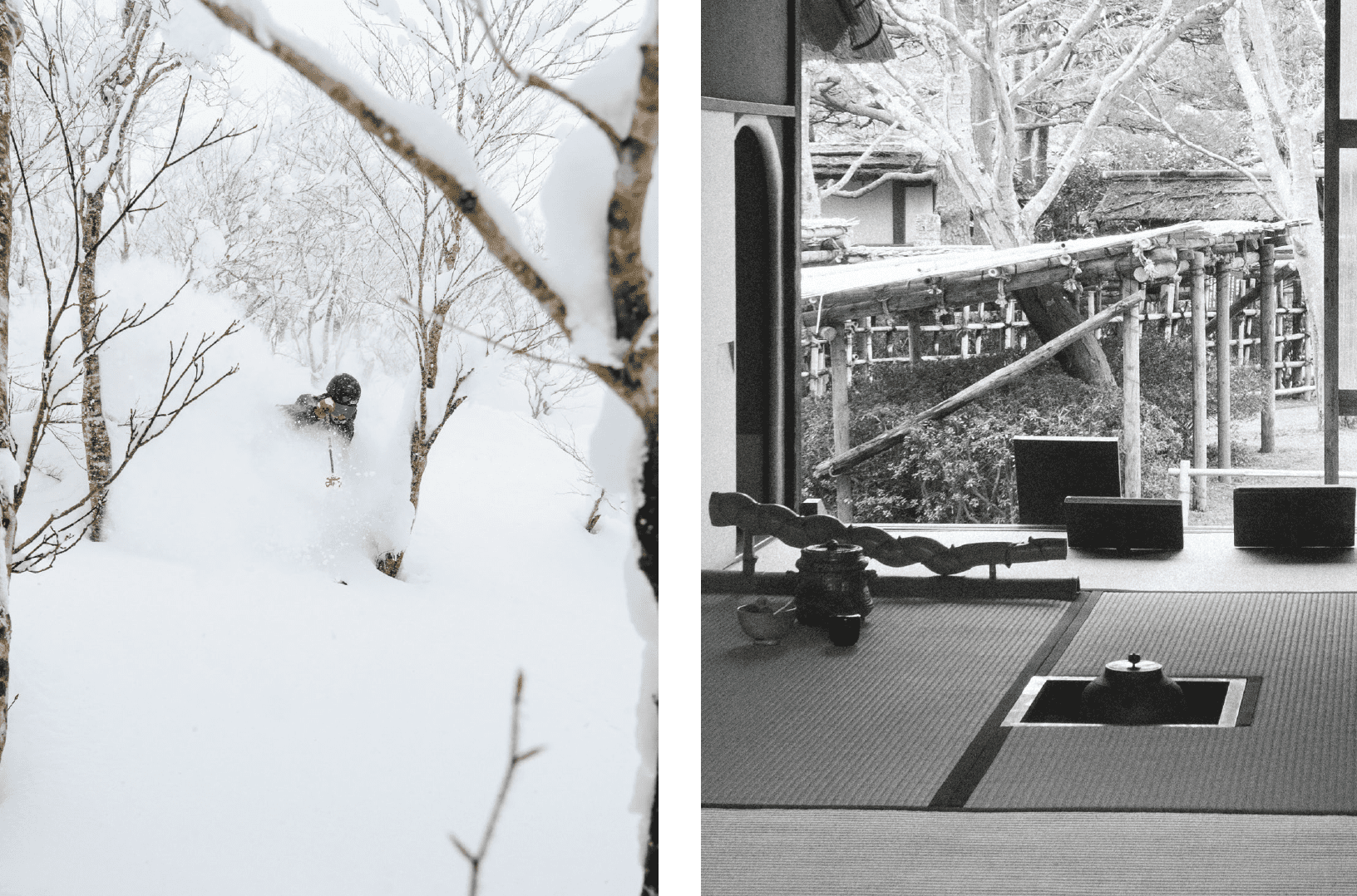

Searching for authentic Japan is incredibly appealing. Aizu, the mountain region of Fukushima Prefecture, has a strong samurai history and is one of Japan’s last ski frontiers, free of Western influence. Fukushima Prefecture is Japan’s third largest Prefecture, and provided the perfect opportunity to create a film that connects with the locals who live, breathe and love Fukushima despite the 2011 Tohoku tsunami and nuclear disaster.

For Mattias Evangelista, former US pro skier and cinematographer, creating a documentary style film to screen at mountain film festivals around the world was the impetus for the making of the movie featuring the local Aizu snow community. The film is truthful and honest and provides a deep insight into the strength of human spirit to overcome adversity. His 22 year old younger brother and pro skier, Micah Evangelista gives his insight into the film ….

Prior to researching the Aizu film project, we had no idea if Fukushima was a known skiing location, or even it it had significant snowfall.

We had heard about the 2011 Great East Japan eathquake that rocked the Tohoku Region and nuclear disaster, but we didn’t know the story of the local Aizu snow community at all. We knew what the rest of the world was told, of the deaths and magnitude of disaster matched only by Chernobyl. TV shows and online videos tout the ongoing danger of radiation exposure still lingering in the area that focus on the area immediately surrounding the nuclear power plant, with no mention of what’s happening in the broader Fukushima Prefecture. And for us, we needed to be assured that Aizu’s 22 ski resorts were safe for us to visit.

We didn’t know a soul there, but we knew of the bloodshed and tears following 2011. From afar, we had seen images of the abandoned landscape at ground zero, which lives on through ruins of destroyed buildings, black bags stuffed with radioactive soil and the engrained memories of locals with no means of leaving. We wanted to learn more, to discover the whole Prefecture and understand the context of the disaster on the Fukushima snow community.

2020 was a low snowfall year on Honshu, Japan’s main island, and that had us concerned as narrow-minded travelers with dreams of waist deep powder. However, we would come to find the area represents much more than one or two face shots, and instead the resurrection of resiliency from the rubble of disaster.

We arrive into the chaos of Tokyo and the million-mile-an-hour paced pedestrians navigating the train station. Fukushima sits about two hours north of Tokyo via bullet train. Entering the Fukushima station, views of Mount Bandai, originally called “Iwahashi-yama” meaning “a rock ladder to the sky” loom out of the small window.

From there, the weaving highway leading to Aizu, the westernmost of the three regions of the Fukushima Prefecture, conjures memories of the Sea to Sky highway in British Columbia. The contrast of water, snow and mountains all blending into one.

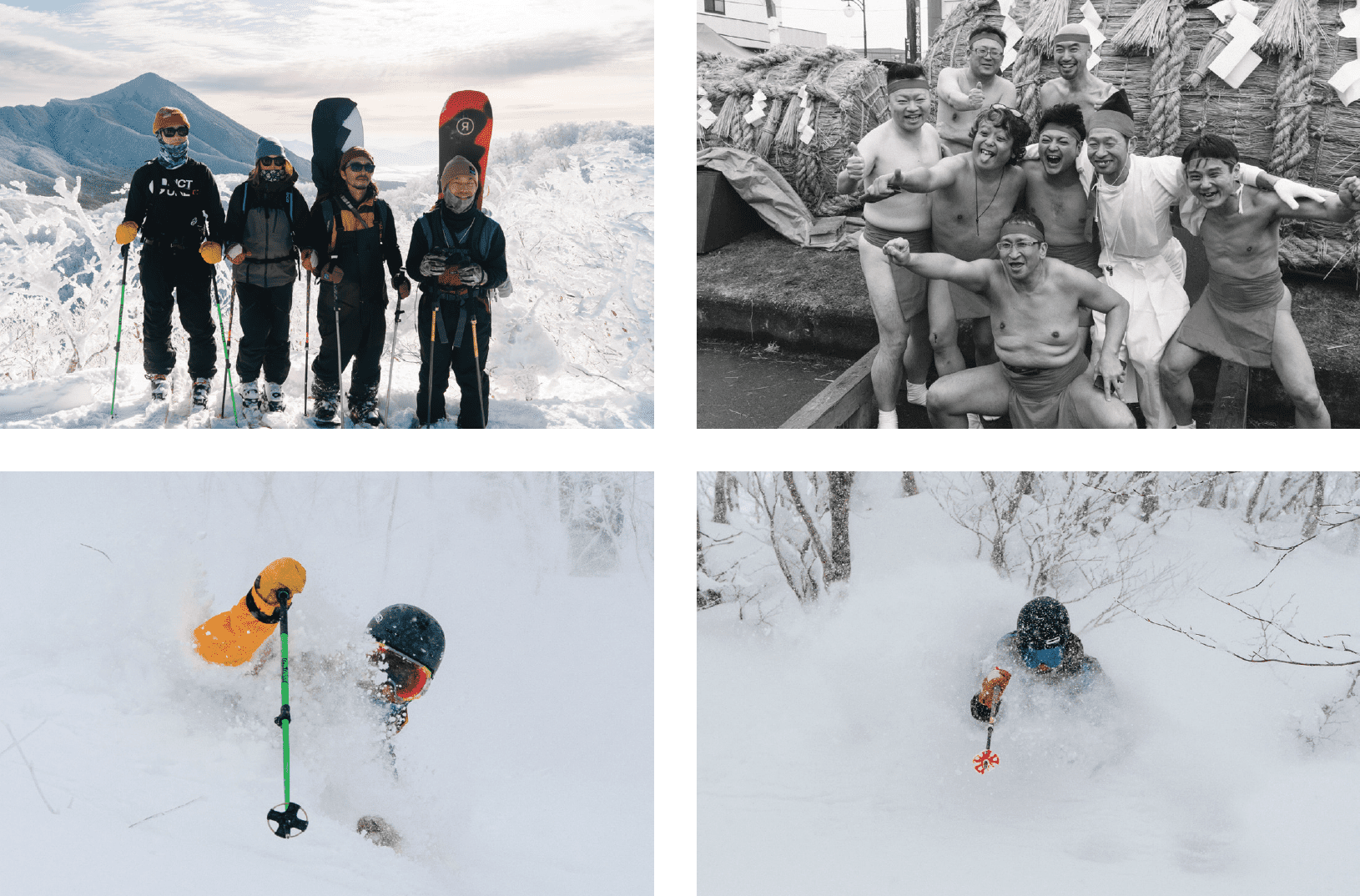

Upon arrival, Keiichi Ishiuchi, the marketing manager for Hoshino Resorts Alts Bandaiand UraBandai Nekoma Ski Area, introduces us to local legend Futa Adachi who has lived in Aizu his entire life. Futa is a ripping snowboarder admired for his effortless style and kind demeanor.

The next day we find him and his friend Hiroki Matsuura in the lodge before opening. Although it is the worst season they’ve had in 60 years, they make the most of it by showing us their favorite hidden spots around Urabandai Nekoma Resort. “I love showing foreigners our mountains if they are respectful of our traditions,” Futa says.

They teach us the words “psycho’ and “yabai,” roughly meaning awesome and amazing respectively. We shout “psycho” at each other as we weave down the empty runs, chasing the rooster tail of powder sprayed into the air from our guides.

After a long day of riding and an afternoon ramen refuel, Futa and Hiroki sit face to face in the now empty lodge, recalling moments from their past that have shaped them as snowboarders and people, and how this region they love has battled with the issues from the earthquake, tsunamai and nuclear disaster.

“We grew up in the same town and went to the same high school,” Hiroki says, “but we didn’t become friends until later in life.” Hiroko didn’t begin snowboarding until he was 18. At that point, he really wanted to be friends with Futa because he was so good at it and had such great style.

“I was raised as a skier,” Futa says. “Around the age of 10 my sister began snowboarding, and like many children I wanted to be just like my big sister, so I too became a snowboarder.” Sixteen years of friendship later, and they’ve explored much of Aizu’s backcountry, constantly pushing each other to their full potential.

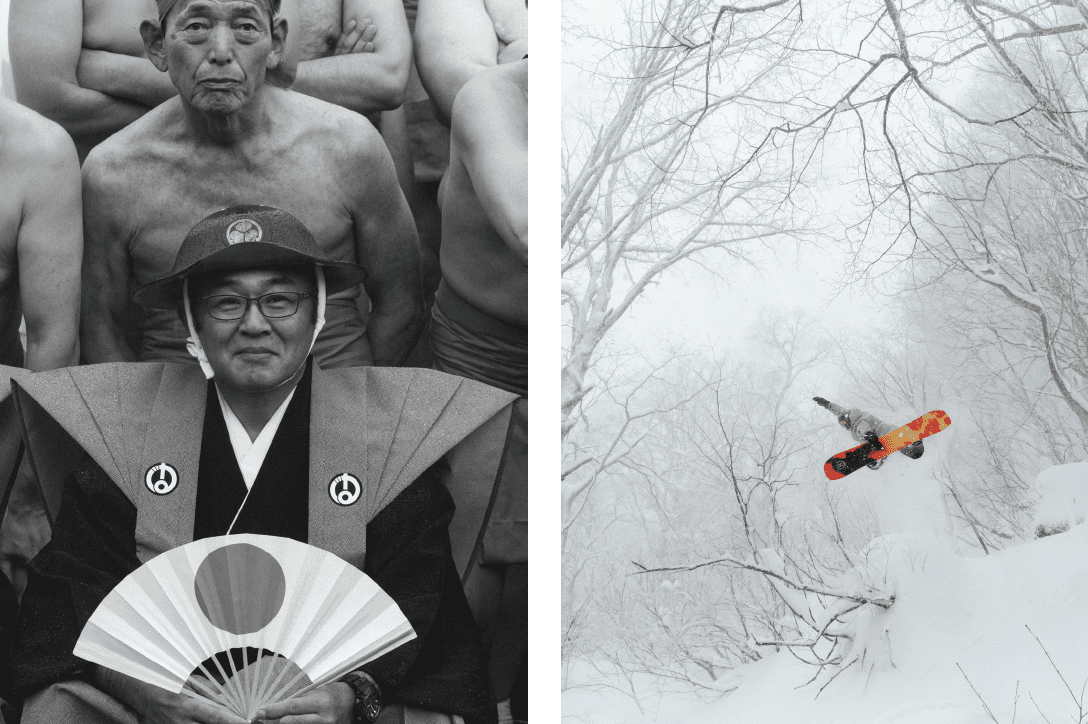

In 2011, a 9.0 magnitude earthquake triggered a 14-metre high tsunami that devastated the entire Tohoku coast. The wall of water flattened coastal towns and flooded the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant. Water rushed the plant, destroying the cooling systems and causing electricity failure, allowing radioactive material to leak out.

Across the Tohoku Region, 18,500 people died and over 160,000 were forced from their homes. As our conversation shifts, so does Futa and Hiroki’s body language. The laughter and smiles that were present just moments earlier vaporise.

“In 2011, when the earthquake and tsunami hit, I wasn’t there with my family,” Futa says. “I wish I was.” He was in Whistler, Canada snowboarding. He checked the news on his phone and flipped on the television to find images of the tsunami hitting the plant. “I couldn’t believe it,” he says.

“I was the exact opposite when the disaster happened,” Hiroki says. “I was here with my family, hoping to start building our life together. We hadn’t been told to evacuate, was our area safe?” They both explain for many locals, it was difficult to leave the place you’ve grown up in. “Your work, family and friends would all be left behind. Part of us wanted to run, but had nowhere to go,” Hiroki adds.

After days of riding and with weary legs, we make plans with Hiroki and Futa to head to the site of disaster to see it for ourselves, over 2.5 hours away from the Aizu mountains. The Aizu mountains were not impacted by the disaster, so we needed to make the long drive to the coast to get the full picture of the Prefecture. En route, we stop at Kitaizumi, one of their favorite surf spots along the coast. Fukushima is home to some of Japan’s best surf and surfers. They’ve brought along their friend Masanobu Miura (Masa), who we’d come to find was a first responder on the day of the disaster.

Masa joins us in our car, and we continue the journey to Ground Zero. As we near the site, the energy in our car shifts. The stoke from surfing and previous days of riding has been replaced by an eerie feeling as the reality of where we are begins to sink in. The exclusion zone is a twenty kilometre radius. The road is lined by abandoned buildings in ruins. The only people around are construction workers stuffing black bags with contaminated soil from the area surrounding the plant.

“This is Namie Town,” Masa says. “From here it is prohibited living. In our fire department, I am the first man to get around (here) after the explosion,” he says. “My boss said, how about you? You go to the power plant to get the people out. I said of course, that is my job,” Before he left, he made sure to put his son and wife aboard a train to Tokyo for safety.

“On the way (to the power plant) I emailed to my friends, I’m very scared. But I have to go,” Masa adds. He stares out the window in silence as the memories of that day flood back. After a few minutes he looks up and points out the window, “That is the plant.”

We step out of the vehicle. The sky is a charcoal black but somehow golden light leaks through the cracks. It feels post-apocalyptic as Futa pulls out his Geiger counter which measures radiation levels. We had measured the geiger counter readings at a 711 carpark at Fukushima City and they were similar to what you would expect to experience in Tokyo, Sydney or San Francisco around 50 kilometres from the nucluear power plant.

When it reaches above 0.5 you should be concerned, Futa says. The counter beeps rapidly and reads over 6.0. After a few minutes, we collectively decide it’s time to leave Ground Zero. The surrounding mountains curbed the spread of radiation when the disaster occurred, leaving the western side of prefecture safe to live in, and it’s time to get back there to the Aizu ski resorts.

“The saddest thing was that the conversation changed,” Futa says. It went from casual conversation about how you’re doing to questions about missing people or people who stopped coming surfing or snowboarding. Despite this struggle, Hiroki explains in the last few years, he has begun to see familiar faces returning to the area, and the reputation of Aizu having a strong community and environment is encouraging people to come back.

“Fukushima people have a strong heart and passion from the past disaster to help our children grow,” Hiroki says. “I don’t think we can bring back the community we used to be, but we can make a community that’s stronger than before,” Futa adds. Much of that passion stems from teaching the younger generation the history of the area and the appreciation of snowboarding.

Futa is a skateboard and snowboard coach when he’s not riding for personal satisfaction. “I want the children to be proud of living in Fukushima,” he says. A group of kids’ session the mini ramp where he coaches for hours, cheering each other on after they land a trick. This support is what helps the community thrive after a long journey of suffering.

“I only wish to have a better future, Hiroki says. “It’s already happening. New winds are coming from the right direction. We will definitely snowboard until we are old. Our style may change, but we look forward to that,” he adds with a smile creasing the edge of his lips.

“If we have a limit, we will pass our passion onto the future generation,” Futa says.

Find out more about the film, the Fukushima snow community and the stories behind it at Aizu film