2019-2020 North American Snow Season Outlook – January Update

The Gravy Train Continues For The Northwest

Mountainwatch | The Grasshopper

Over the last month, the Gulf of Alaska has been a hotbed of cyclonic activity that has sent an endless procession of snowstorms streaming down from the northwest, piling massive amounts of powder over resorts in Canada, the Cascades and most of the Rockies. It’s the gravy train that just keeps on giving, and all signs indicate that it ain’t done yet.

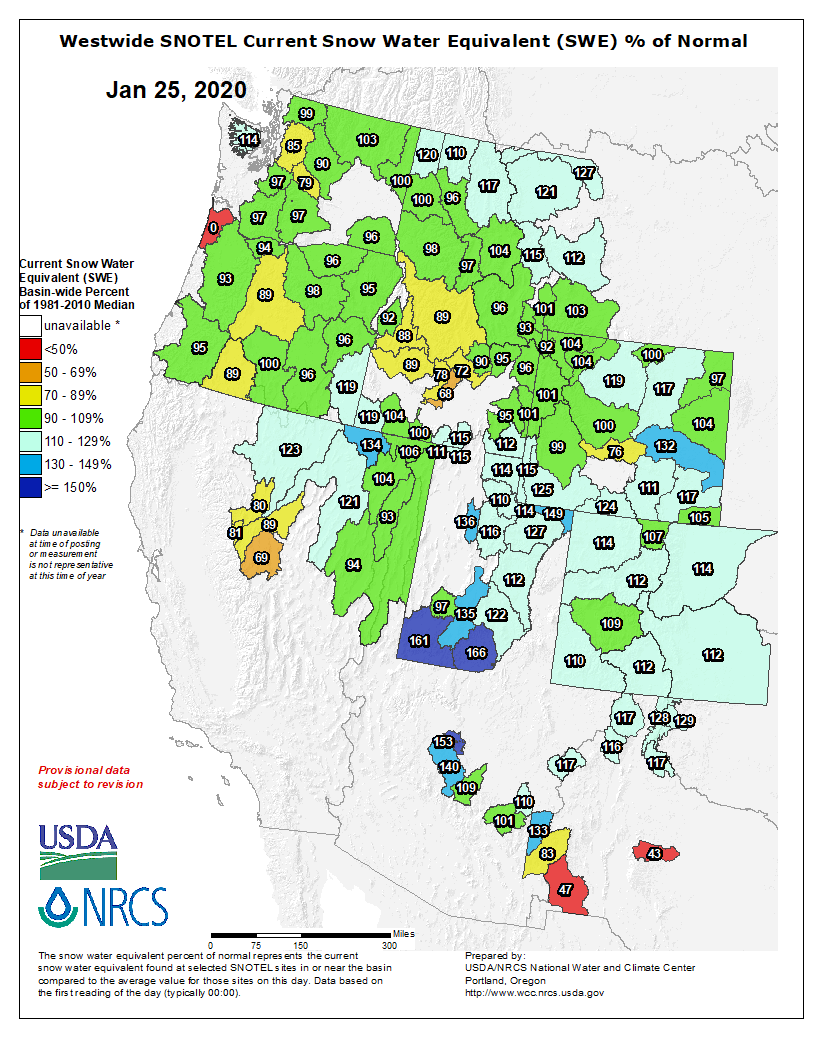

The biggest gainers over the last month have been in Canada and the Cascades. Snowfall here has gone someway to make up for the lack of it during the early season, and snowpacks – believe it or not – are still sitting just shy of average for this time of year. On the other hand, resorts farther inland in British Columbia and Alberta are sitting on 20-40% more snow than usual.

On the other side of the coin, the Sierras have slowed down after a great start to the season. The snowpack there is now running at a 20-30% deficit compared to average. Squaw Valley is reporting that 60-120cm has fallen so far this January, while only 28cm has fallen at Mammoth, which is a mere dusting compared to the 230cm that fell last January.

Good, consistent snowfalls through much of the American Rockies have generally improved things in Idaho and Montana, although resorts in the Sawtooth Range, such as Sun Valley, Soldier Mountain, and Bogus Basin are still lagging behind.

Wyoming, Utah and Colorado have all maintained their excellent run, with Jackson Hole famously kicking off 2020 with 3m of powder during the first two weeks. Snowpacks are average or above in these states, which says a lot considering several meters should fall in an average year.

How aboot that weather, eh?

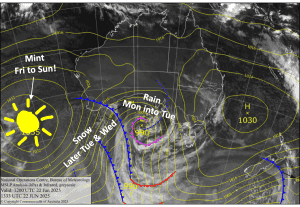

The weather pattern of late has seen fronts spilling out of the Gulf of Alaska and sweeping inland and south, where they have often briefly spun into lows over the Great Plains, ensuring snowfalls spread from the Northwest to the Central Rockies (Utah, Wyoming & Colorado).

Sea level pressure anomalies from the previous 30-days. Blue & purple shades show the storm track extending inland from the Gulf of Alaska to the Great Plains in the south, while ridging affected the Sierras. Source: NOAA

Short-term models expect this pattern to continue at least through the first week of February. Longer-range ensemble models suggest this may continue into the second week too, followed by west-wide ridging (high-pressure = less snow) through the second half of February with the possibility of troughing (low-pressure = more snow) affecting the Sierras and southern Rockies towards the end of the month into early March.

We must tread with caution here as these longer-range ensemble models are lovely to look at, but are wrought with dangers. To get an overall idea of how things look on the long term, we use seasonal forecasts that span a three-month period (a season) in order to iron out some of the crinkles and inaccuracies.

Who’s driving this thing?

The overall pressure patterns of the previous month look similar to a negative phase of the Pacific-North America Pattern (PNA), which tends to bring more snow to the western side of North America. Indeed, the index that tracks this teleconnection took a dive early-mid January between hovering around neutral values.

The Arctic Oscillation (AO) has just come down after a strong positive phase, which, in a roundabout way, usually brings more snow to the west, especially during neutral phases of the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Negative phases of the AO tend to get more attention from media because they often result in cold outbreaks, but this is usually restricted to areas east of the Rockies. Here in the west, a positive AO can work in our favour.

The tropical Pacific tends to influence both the PNA and AO, which are also closely correlated, but with a neutral phase of the ENSO locked in for the rest of the northern hemisphere snow season, these teleconnections are free to wander. We can’t accurately predict the PNA and AO beyond two weeks, but forecasts from seasonal models can leave a trail of breadcrumbs for us to follow.

Seasonal forecasts indicate low pressure will persist over the North Pole, leading to an overall positive vibe, both in terms of the AO index and west-wide snowfall. The Aleutian Low is also expected to remain weak, which as I wrote in the previous outlook, tends to increase snowfall in the west, especially over the Coast Mountains, the Cascades and the Rockies as far south as Wyoming.

A weak Aleutian Low is only part of the picture that makes up a negative phase of the PNA. Although models don’t explicitly forecast it, a weak Aleutian Low is likely to lead to low pressure over northwestern North America; it’s exactly what we’ve seen this past month and is another key ingredient of a negative PNA.

Still snowy in the north and NOAA agrees

Taking the above blurb into account, the Coast Mountains and the Rockies as far south as Wyoming, with the new inclusion of at least the northern half of the Cascades, still stand a good chance of above average snowfalls over the next few months.

We’re likely to see average-or-below snowfalls in the Sierras, although the snow pendulum has been tipped to swing down south during the end of February and early March. The remainder of the Rockies (Utah, Colorado & New Mexico) remains on the fence where snowfalls could swing either way.

The good folks at NOAA haven’t changed their forecast and continue to back me up. Source: NOAA

This is no great change from the previous outlook, but then again we don’t expect the climate and seasonal models to flitter to and fro willy-nilly. NOAA’s outlook also hasn’t changed and is consistent with my predictions. At the least, what I hope to have done is highlight the underlying forces at play here – the canvas upon which we’ll paint our weather masterpiece.

That’s all from me folks. I’ll update this outlook in another month or so. If you’ve got a different theory on what’s going to happen this winter, or just want to provide feedback, then please hit me up on the discussion below. Or you can follow me on Facebook.