Hakkoda, Aomori – A Ropeway That Rewrites The Japanese Ski Experience

Mountainwatch | Matt Wiseman

Hakkoda is unlike any other resort I’ve skied in Japan. Perhaps the world. I’m told it bears some resemblances to Asahidake and Kurodake ski areas on account of the large ropeways that service them all, but Hakkoda, on the northernmost tip of Honshu is very much its own (wild) animal.

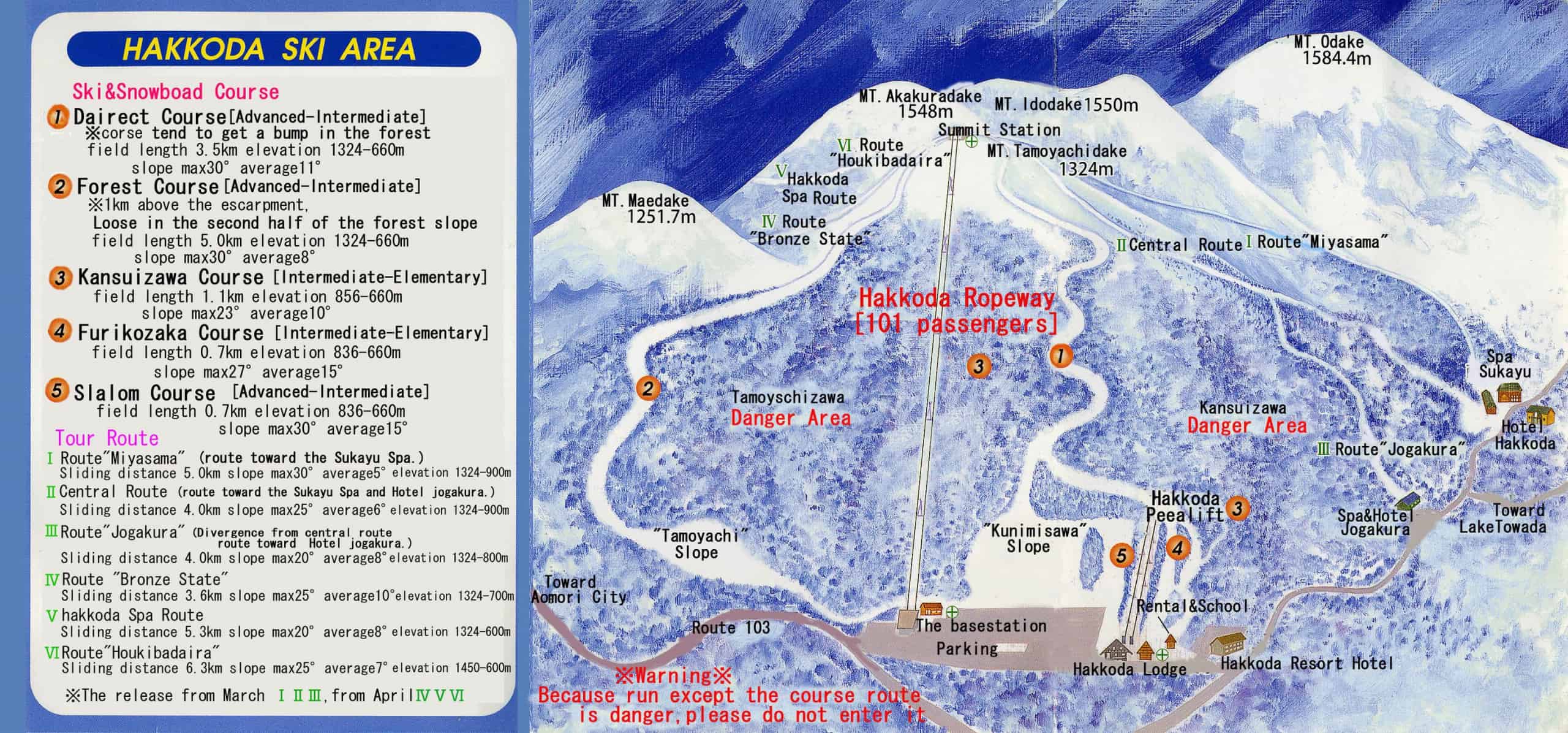

The skiing in ‘resort’, if you can call it as much, is probably the closest thing to backcountry skiing you can have where a lift is still responsible for getting you to the top. On the frontside of the mountain, the options are both limited and endless. Two designated trails diverge from the 1,324m peak where the ropeway concludes its 10 minute, 650m vertical ascent. There’s a 5km forest course and a 3.5km direct course that both hem in the frontside of the mountain. In between the two, high above, exists the 2459m long ropeway, and below countless acres of skiable terrain, all of which you’ll have practically to yourself.

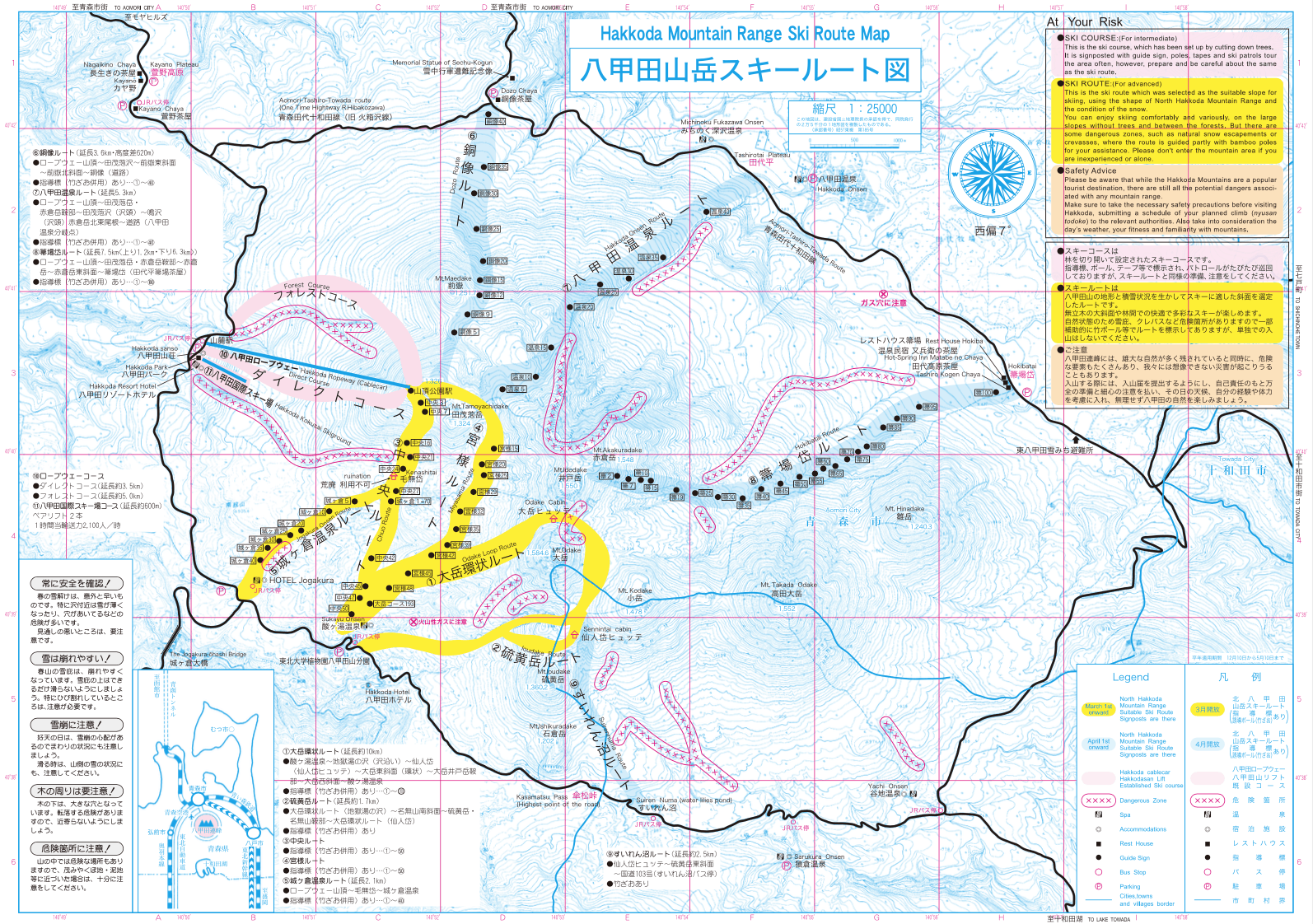

The Hakkoda trail map says both very little, and everything about the place at the same time. Very little because there’s only two noteworthy runs to speak of – run one and run two. Runs three, four and five, sprout from a typically quaint Japanese double chair, operated by a separate lift company on the looker’s right and are only really worth riding if the ropeway is suspended because of high winds. Where the map speaks volumes, is in the brush strokes that bring it to life. Hakkoda is a distillation of core Japanese skiing, and the blue, hand painted trail map says as much.

Over the four days I spent there in late February of this season, I counted six westerners and 3 of whom I heard speek fluent Japanese. In place of the Australian, American and Nordic powder hounds I’d expect to share a gondola with in the more discovered reaches of Japan’s ski resorts, there were only advanced Japanese skiers and boarders and a handful of Chinese boarders. On my first day there, pole position in the ropeway line was held by two Japanese ladies in their 60’s, both wrapped in Gore-Tex, shouldering packs heavier than mine and gripping the latest and widest powder skis from DPS with tech bindings. Hakkoda is no joke. As far as the core skiing and boarding experience goes, it might be Japan’s version of France’s cult destination, La Grave – which also has only two pistes. But even La Grave has two more groomers than the ropeway. Run’s one and two, while being designated ‘trails’, still don’t feel the cold touch of a grooming machine, or at least didn’t during my stay, so in effect, the whole resort is just one gigantic off-piste playground.

I visited Hakkoda on the 19th of February this year, during what can only be described as a devastatingly below average snow year for the whole of Japan. At that time, friends in Hokkaido were lamenting the rain that seemingly followed each snowfall like a shadow and those in Hakuba shared images of a lower mountain looking uncharacteristically brown. Such was not the case in Hakkoda. While locals still apologized for the so-called lack of snow, 2-3 metres of the stuff hedged the side of the road on the way into the resort and 30cm* lay in wait for my first day of riding.

*While 30cm fell on the afternoon and evening that I arrived, it skied a hell of a lot deeper, since the ropeway had been suspended for three days prior due to high winds. While this might raise alarm bells for those looking to visit, I was told three days was an especially long time for the ropeway to be on hold. Even so, be prepared for at least one down day if spending a week or more riding here.

Despite the Ropeway’s tendency to close when winds topped 25m/s, in my experience, the Hakkoda Peak double chair will spin in a gale, and there’s enough skiing on and around its slopes to entertain for at least a day. The silver lining of course when the ropeway closes, is what awaits you when it reopens. And I wasn’t the only one who eagerly anticipated it’s opening, as roughly 150 locals were in line with me to get after it half an hour before the opening at 9am on a Wednesday.

While this might sound like a lot, it only equates to one and a half cable cars and was ultimately the sum total of people on the hill that entire day. Where they all went is another question, because of the 6 laps I managed to squeeze into that first day, I passed just a handful of skiers and boarders on my way down each time, and barely crossed a track other than my own whilst doing it.

It wasn’t long until I discovered where in fact the majority of local riders went as I joined them the following day in the backcountry. As sublime as the riding in resort was, the same and more can be said for the terrain beyond the ropeway.

I was lucky enough to be taken beyond the resort boundary by experienced local guide Kudo Masakazu of Hakkoda’s Mountain Academy. Hiring an experienced guide like Kudo-san will not only lead you to the deepest snow on the hill via the path of least resistance on the skin track but you’ll also get there in very good spirits. Kudo’s stoke and love for skiing powder personified Hakkoda as did his accommodating, albeit broken English.

If that’s not enough of a reason to join a guided group, on each of the three days prior to our own ski tour, Kudo-san informed us ski patrol and rescue services were called in the evening to find unguided, unreturned skiers and boarders. While all were found without issue, the same cannot be said for the soldiers of the Japanese Fifth Infantry Regiment more than a century before, whose story is now lore.

“Have you heard the story about the Hakkōda Settchū Kōgun Sōnan Jiken?” asked Kudo-san, which he translated to the ‘Hakkoda Mountains Incident’. We pulled off the skin track on a little bench before the next rise and half dozen switchbacks looming above. Kudo then told us the fatal story of the 210 Japanese soldiers who, on January 23 1902, attempted to secure a route through the Hakkoda Mountains in the event the roads and railways were destroyed by the Russian Navy. As fate would have it, this attempt coincided with the lowest temperature ever recorded in Japan of -41ºC on January 25. Of the 210 soldiers, 199 perished in the blizzard conditions. To this date, it marks the most lethal disaster in modern mountain climbing, the reason Hakkoda’s mountains are so revered among locals and across Japan and but another reason to hire a guide.

With ten peaks to choose from in the Hakkoda Mountain Range, we resumed our push for the low hanging fruit summit of Mt Maedake, a 1,251m outcrop above a sea of snow monsters and the so-called dozo ski route back down. ‘Dozo’, for the uninitiated, is Japanese for ‘go ahead’ or ‘go first’ which Kudo-san kindly permitted me to do. A break in the clouds provided views out to Aomori city and the Sea of Japan as I glided down the 30-degree planar powder slope and into the frosted tip trees below.

Ready to reattach my skins and climb back up and over into the resort, Kudo-san had no intentions of transitioning. Instead, we punched through the trees and onto the road that wrapped around below. There, we were met shortly by the guiding companies’ bus, brimming with other happy customers who’d skied different lines and emerged higher up on the road that encircled the mountain. If this isn’t a final reason to hire a guide, I don’t know what is. Returning to the resort we toured and skied until the ropeway closed for the day at 4.20pm.

Intrigued by Hakkoda’s formative history I couldn’t help google translate ‘Hakkoda’ as I enjoyed the height of the Hakkoda après scene in a vending machine Sapporo while sumo wrestling played in the background of my hotel room.

If Hakkoda calls you. Answer.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………..

More on Hakkoda; how to get there, accommodation options and non-skiing activities here.