2018 Australian Snow Season Outlook — Vanilla… mmm, Not Bad

Models pointing to average temps and precipitation

Mountainwatch | The Grasshopper

The 21st of March marked the Autumn Equinox in the southern hemisphere, the time when the Sun passes over the equator to hang out in the northern hemisphere and when nights become longer than days. It also serves as a reminder that snow is just around the corner and that we should start getting excited.

Snow is just around the corner, it’s time to get excited. Image: Harro/Buller

It’s been a real mixed bag for the northern hemisphere season. Japan was having a bumper season, but slowed down at the end of February, while American resorts were off to an excruciatingly slow start, but then ‘Miracle March’ happened and resorts are now basking in hefty spring dumps. It was a similar story for Australian resorts last year. A dismal season turned into a real cracker late winter and early spring when the ‘Blizzard of Oz’ struck and the snow depth raced up to a whopping 240 cm at Spencer’s Creek — well above the average of 195 cm. Are we in for a similar story this season? Well, I’ve managed to have a cheeky peek at what Ullr and Skadi, the god and goddess of snow, might be serving up this season. Bon appétit.

ENSO & IOD — neutral as vanilla ice-cream

In a nutshell, the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) represents the differences in sea surface temperatures (SST) between the east and west of the Pacific Ocean near the equator. The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is the same, but for the Indian Ocean. Warm water can slosh from side to side in these two oceans and have far-reaching influences on weather patterns around the globe. Check out an earlier article I wrote for a more in-depth explanation on the ENSO.

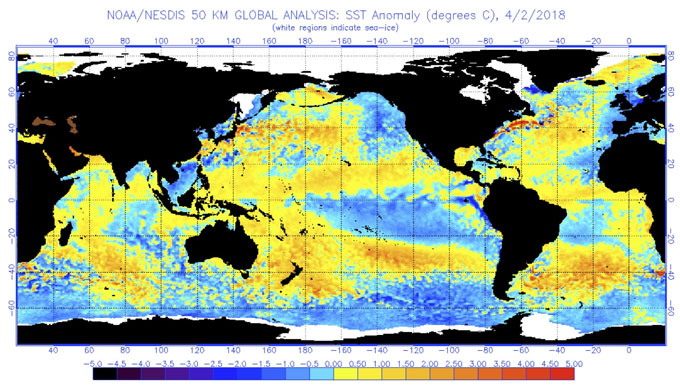

Global SST anomalies showing waters around the equator of the Pacific Ocean are slightly warm in the west and cool in the east, but still lie within a neutral state of the ENSO. Waters in the Indian Ocean aren’t much different from west to east, with the IOD also neutral. Note the warm waters in the Tasman Sea and near Tasmania. Source: NOAA.

The weak La Nina conditions we had during spring and summer, representing warm water in the west and cold water in the east of the Pacific Ocean, are now fizzing out. Although sea surface temperatures surrounding the equator are still a bit nippy in the east, they lie within the neutral range of the ENSO. Major climate models all agree that these waters will continue to slowly warm through winter and spring, but should remain within the neutral range.

Likewise, the IOD is currently neutral and the majority of climate models keep it that way through winter. A couple of models however, including the Bureau of Meteorology’s (BOM) very own POAMA, hint that it could swing negative. A negative IOD means warmer waters northwest of Australia can feed moisture into frontal systems as they track over the Aussie Alps, thereby beefing up precipitation which hopefully falls as snow.

Peak snow depths vary wildly during neutral ENSO years, but if we can be overzealous for a moment and cherry-pick a little, these seasons can bring good fortunes to the Australian Alps. As I mentioned, 2017 was a neutral ENSO winter and was only the second time since 2004 to have an above average peak snow depth; the first time was back in 2012, and surprise, surprise, we also had neutral conditions that winter.

Remember the ‘Blizzard of Oz’? This happened during a neutral ENSO. Are we in for a rerun this season? Image: Perisher

It’s well known that El Nino’s are not good for snowfall in Australian. However, things aren’t that simple when comparing neutral and La Nina episodes. Did I just hear you sigh? I know it’s complicated and you can feel an explanation coming, but bear with me, this is interesting and I’ll try to keep it brief.

A recent study looking at the ENSO’s influence on Aussie snow found that between the years 1954-1983 La Nina seasons averaged about 10% deeper snow than neutral years. However, between the years 1984-2014 La Nina had a mood swing and provided about 20% less snow than neutral seasons. To complicate matters further, negative IOD’s can bring La Nina out of her recent slump to provide optimal snowfall conditions, slightly trumping neutral years.

This flip-flop nature of La Nina’s mood could be explained by the fragility of snow conditions in the Australian Alps – a marginal Alpine environment where snow hangs in the balance. Due to the long-term warming trend in the Aussie Alps, La Nina seasons now tend to be too warm. It’s no secret that the key ingredients for a good snow season is the combination of a lot of precipitation and low average maximum temperatures (average minimum temperatures statistically have a low correlation to snowfall). It just so happens that a negative IOD can provide exactly this. So, when La Nina and a negative IOD team up, the scales can be tipped to favour deeper than average snow. A positive IOD has the opposite effect, warmer and dryer conditions for southeast Aussie, while a neutral IOD just happily sits in the middle, simple.

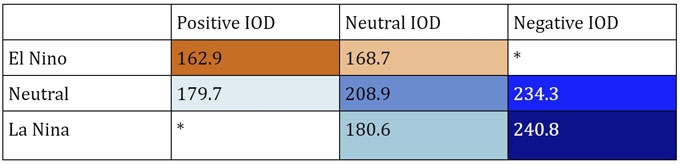

Why have I bothered to explain all this? Because we would like to know how this season stacks up compared to others. Check out the table below that ranks climatic conditions. You’ll see that with a neutral ENSO and IOD we’re coming in at 3rd, with an average peak snow depth of 208.9 cm — that’s above average. A negative IOD, like the BOM are suggesting, will bump us up to 2nd with whopping depths of 234.3 cm — that’s vanilla ice-cream dipped in chocolate with sprinkles on top!

Average peak snow depths at Spencer’s Creek (cm) during ENSO/IOD years. (* Denotes years where the sample size is too small). A Neutral ENSO & IOD puts this seasons prospects in 3rd place compared to other combos.

But let’s not get too carried away my fellow froth merchants, because neutral ENSO’s are temperamental, we need to sniff around for more clues as to what’s cooking in the kitchen.

SST — an unsolved mystery

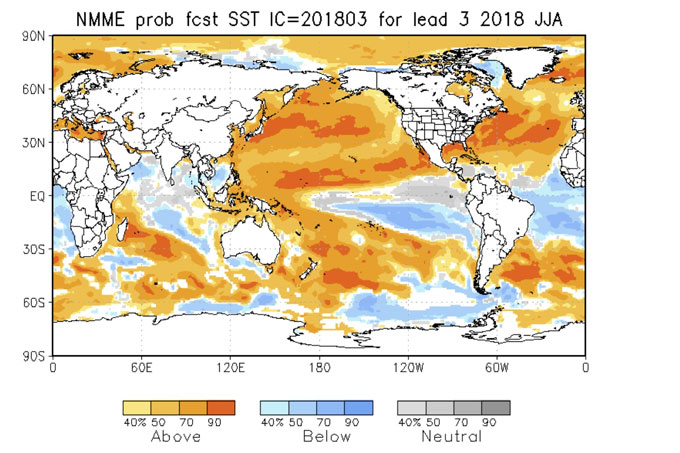

SST anomalies for June, July & August. Above average SST are likely for the south Tasman Sea and large parts of the Southern Ocean. Source: NOAA

SST in the south Tasman Sea rose sharply during the tail end of 2017, with climatologists declaring it a marine heat wave. All sorts of temperature records were broken in areas bordering these waters, especially in southeast Australia and Tasmania. Warm waters in this region is nothing new; over the last half century or so, the East Australian Current has expanded southwards to lift SST by about 2°C on average.

Although the marine heat wave has chilled out a little bit, SST are still above average and there is good agreement between climate models that this will continue though winter and spring. I’m particularly flummoxed by the warm anomalies predicted for the Southern Ocean because this is where the bulk of our weather systems come from. Warmer waters should add a shot of gin to these systems, but it is hard to say how it will affect snowfall in the Aussie Alps. It’s tempting to say that temperatures will rise a little, thereby tipping the scales to make rain more likely than snow. However, I’m yet to find any hard evidence on the matter so it remains an unsolved mystery.

Climate models — about average

Those of you who have checked out the BOM’s climate outlook will have squinted at the Aussie Alps and noticed that the next three months should be wetter than average. Hopefully this means more snow, but it’s hard to say. The important variable to look at is average maximum temperatures, and the BOM are picking this to be about normal. However, the BOM is also going for warmer than median minimum temperatures, especially during April and May, which may not bode well for preseason artificial snow making. The BOM’s outlook is likely a response to the warm SST in the south Tasman Sea, which is consistent with other climate models too.

Looking to July and beyond, climate models tend to get a bit hazy and contradict each other, but there doesn’t seem to be any big push in either direction of a good or bad season — so we’re looking at adding another scoop of vanilla to the heap. The only stray from average conditions was the hint of a slight drying off and a dip in average temperatures during late winter and spring, potentially giving snow machines the chance to really fire up.

We need to talk about SAM

Another index that could add a bit of zest to the season is the Southern Annular Mode (SAM). SAM is related to the north/south position of the belt of westerly winds roaring around the Southern Ocean. Cold fronts and storm systems lie within this belt, and a negative SAM brings them in contact with the Australian Alps to deliver lower temperatures and healthy doses of snow. A positive SAM has the opposite effect by pulling the westerly belt too far south. In the last 50 years or so, these westerly winds have intensified and shifted southwards a little, possibly adding to the woes of the long-term decrease in Australian snow.

SAM really is a force to be reckoned with. Its correlation with peak snow depths are slightly stronger than both the IOD and ENSO, and average peak snow depths differ by 32% between positive and negative phases. Unfortunately, there is no long term forecast for SAM and about 30% of snow seasons experience both positive and negative phases, so persistence forecasts will only get us so far. On that note, we are currently experiencing a weak negative phase and short-term forecasts keep it that way for most of April; fingers crossed that persistence will pay off this season.

Climate models can however leave clues as to what SAM may do in the distant future. NOAA’s climate model is picking lower than average pressure and stronger westerlies over southeast Aussie early this winter, hinting at a negative SAM. During late winter and spring, that flips around with higher pressures and weaker westerlies, suggesting SAM will change to a positive phase and destroy all our hopes and dreams. Before we get too dramatic, remember that was only one model and I can’t draw any meaningful conclusions from other models, so we’re best to remain cheerful until closer to the time.

Summary

This season’s outlook is about as vanilla flavoured as you can get, but that’s not a bad thing. Notice I’ve added sprinkles.

With a neutral ENSO and IOD on the cards, as well as climate models going for about average temperatures and precipitation during winter and spring, it looks as though Ullr and Skadi are whipping up a big batch of vanilla ice-cream this season. Not that vanilla is bad, I actually quite like it, and on the scheme of things it comes in as the 3rd best option when comparing other flavours of climate options. There appears to be no major push or pull towards a good or bad season, so other climate drivers, such as SST or SAM, may have a greater influence. The fickle nature of seasonal forecasting is exacerbated for Australian snow as individual events can have large contributions to the total snowfall; one or two misplaced fronts can lead the season astray.

At this early stage, I estimate that we will have a fairly good start to the season, then a slowish late winter. I’m leaving the door open for a spring dump, possibly even a rerun of the ‘Blizzard of Oz’ but that might be going too far. Maximum snow depths should lie within a range of 180-220 cm when comparing to a long-term average of 195 cm at Spencer’s Creek. The potential for artificial snow making may be hampered during the preseason due to warm and wet conditions, but later in the season snow machines will get their chance to shine.

Hopefully I have shed some light into the season that is currently being brewed up. If not, then at least I’ve whetted your appetite and got you salivating for the upcoming season. I’ve given myself plenty of leeway in my predictions, but as the season progresses I will narrow it down. So, stay tuned.

I’ll update this outlook at the beginning of May as the excitement builds. If you’ve got a different theory on what’s going to happen this winter, or just want to provide feedback, then please hit me up on the discussion below. Or you can follow me on Facebook.

Grasshopper.

With the countdown to season 2018 well on its way, Falls Creek are gearing up for the new high speed quad Eagle Chair to start turning from opening weekend. Get to Falls Creek this snow season and check it out for yourself!

Sign up to updates from The Grasshopper