Grasshopper’s 2024 Australian Snow Season Outlook – May Update

Mountainwatch | The Grasshopper

After the first snowfall in early April 2024 there hasn’t been much in the way of fresh snow across the Aussie ski fields. That looks to change this weekend when a dusting of snow is expected – unfortunately for us, large amounts are unlikely. Across next week, there’s little sign of sign of snow in the forecast, but snow making conditions become more favourable as temperatures trend cooler overnight and dry weather prevails. However, there are no strong indications of snow in the last week of May either.

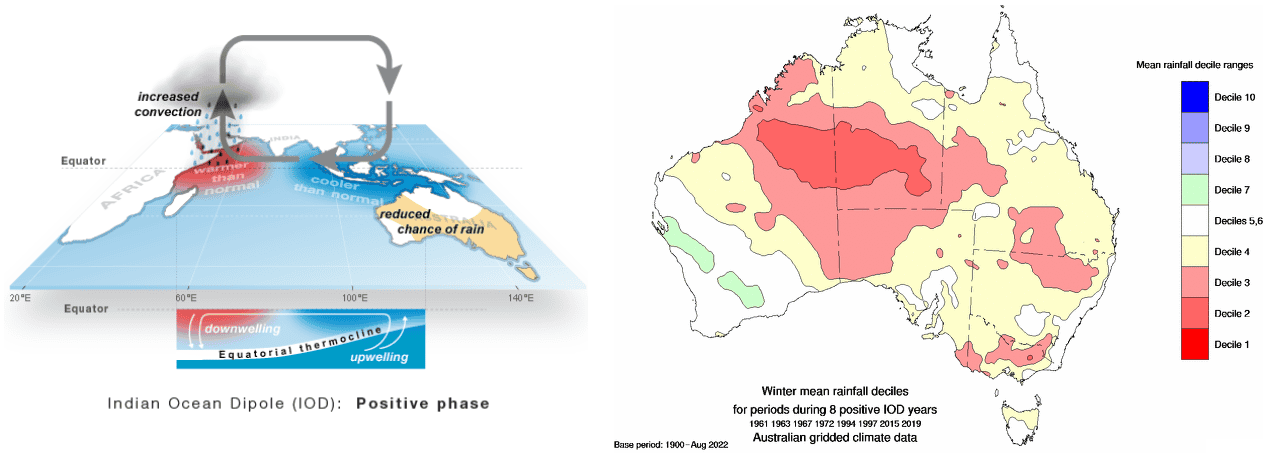

That’s the forecast for the next week or so, but what about beyond? To get an overall view of the upcoming season we need to look at the main climate drivers that impact Australia’s weather. The first of these is the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), which describes large scale ocean and atmospheric patterns across the Indian Ocean Basin.

During March and April observations were pointing towards a developing positive IOD, but May conditions suggest the formation of positive IOD may have stalled. A positive IOD means warmer waters set up near the Horn of Africa and relatively cooler waters lie off the northwest coast of Western Australia. Positive IOD is associated with drier weather across central and southern Australia in winter and spring (including the ski fields), and poorer snow seasons. Most international models have a leaning towards a positive IOD during winter, with spring more up in the air.

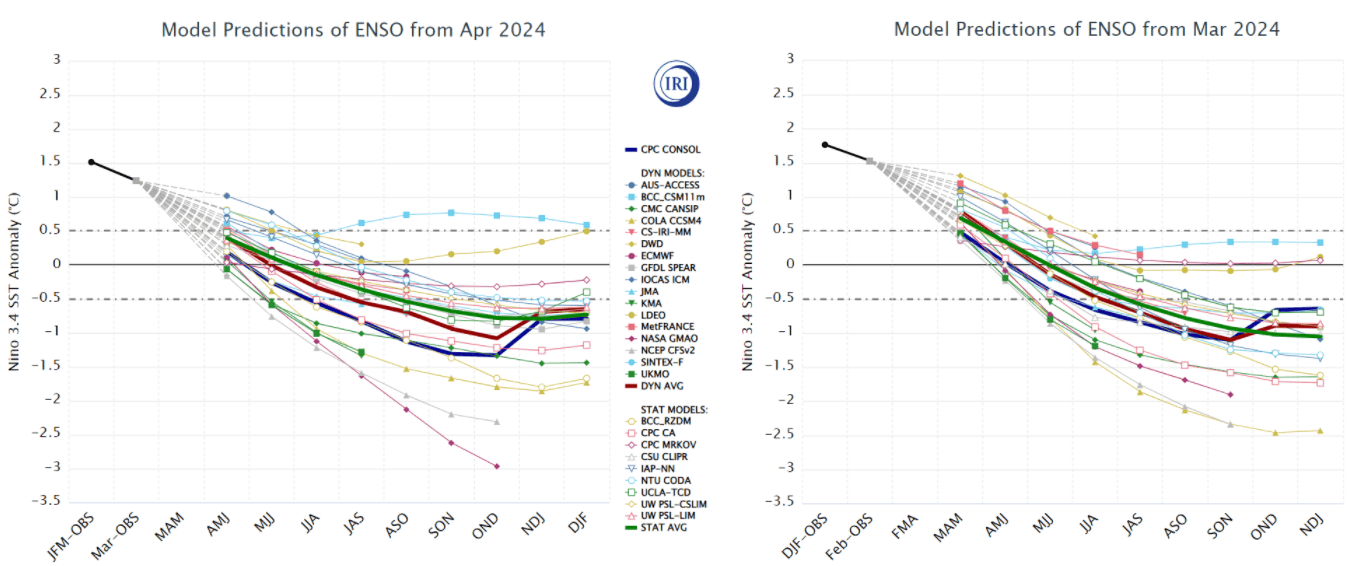

Models split on La Niña

The other main climate driver, which is more well known, is the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO for short). It describes large scale ocean and atmospheric patterns across the Pacific Basin. ENSO is now neutral after sitting in El Nino territory earlier this year.

Many climate models have been predicting a shift towards La Nina conditions this winter or spring, and some have been beating this drum quite loudly. In recent updates there are still many models forecasting a La Nina regime to develop, though some have a comparatively weaker signal, and some are looking at an onset later in the season. The BOM’s model continues to be lukewarm about a return to La Nina, as are other renowned models such as the European Centre model. From the US, NOAA’s modelling is still going for La Nina, but it looks to be delaying the onset a little compared its forecast issued in April 2024.

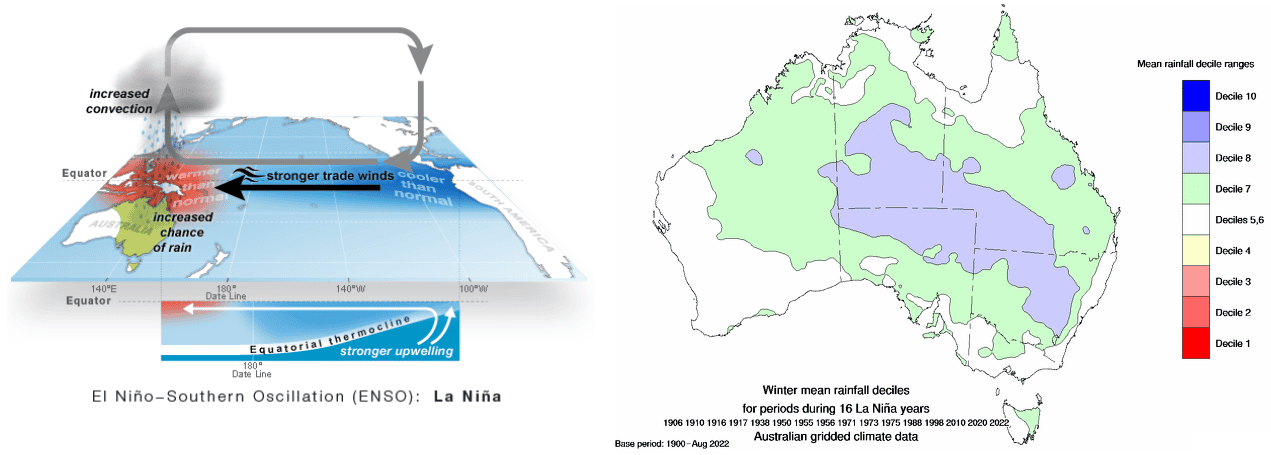

La Nina brings wetter conditions to much of eastern Australia during winter and spring, with more convincing odds of wet weather in spring. In the past, this often brought an increase in snowfall, but over the last couple of decades this hasn’t been the case. Rising temperatures have meant that the chance of snow is lower, and the increase in rainfall can even wash away the snow base at lower elevations

Here is where it gets spicy, though: La Nina and positive IOD are a rare combination. We don’t see them occurring too frequently, and its more common for La Nina to develop in conjunction with negative IOD (also more common to see El Nino and positive IOD in lock step). Will wet La Nina win out this season, or the drier positive IOD? And what does it mean for snow?

There have only been two times when La Nina and positive IOD combined together in recent history – in 2007 and back in 1967. That’s according to NOAA, the BoM has different thresholds for when they declare El Nino/La Nina and positive/negative IOD, but that’s a whole other kettle of fish that we won’t get into. With just these two previous occurrences there isn’t a lot of data to go off. As I mentioned in last month’s outlook, while neither 2007 nor 1967 were bumper snow seasons, they also weren’t completely terrible, both characterised by a couple of larger snow events.

Snow events are often associated with so called “cold outbreaks.” These bring cold polar air (and snow) to southern Australia during winter and are related to the belt of strong frontal systems that moves around the southern hemisphere. The northward extent of these storms is hard to predict more than a couple of weeks in advance and usually occurs with a negative SAM (Southern Annular Mode). Outside of these blasts of cold air, daytime temperatures for the upcoming winter are expected to be warmer, with modelling strongly favouring a warmer season overall. These warmer temperatures could result in a shorter snow season – by staying warmer in early winter and then warming up sooner in spring.

Wrap Up

The first half of the season is looking drier due to the influence of an emerging positive IOD. But clear nights and drier conditions are often good news for artificial snowmaking which could help top up any shortfall. Later in the season, La Nina looks more of a chance and could bring some increased precipitation. No matter how the climate drivers pan out, though, they only typically account for about a quarter of snowfall variation – the rest is natural variability. Cold outbreaks and snow bearing systems are hard to predict more than a couple of weeks in advance; smart money is on keeping plans flexible, so you can capitalise on the best conditions.

As we all know the best way to do that is to keep a handle on short-term weather forecasts, which you can do right here on Mountainwatch with top-of-the-line model data and my daily forecasts which start a couple of days before the opening weekend.

That’s it from me folks. If you’ve got a different theory on what’s going to happen this winter, or just want to provide feedback, then please hit me up on Facebook and hit the follow button while you’re at it.