Grasshopper’s 2024 Australian Snow Season Outlook – Potential La Niña and Above Average Temps

Mountainwatch | The Grasshopper

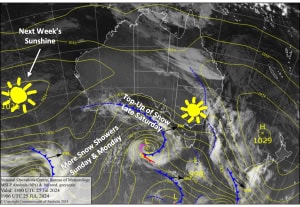

The first snowfall of 2024 came down in the Aussie Alps early last week, just a dusting of pure bliss to whet the appetite for the fast-approaching snow season, which kicks off in just under two months. The snow will have disappeared by the time this reaches your eyes, but will no doubt have left you wondering whether this is going to be our year.

First and foremost, we’ve got to check in with what’s going on across the tropical Pacific Ocean, a key influencer in Australia’s climate. Here, the seesawing of sea surface temperatures between the east and west has a major impact on weather patterns across the globe, and is what we call the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO for short.

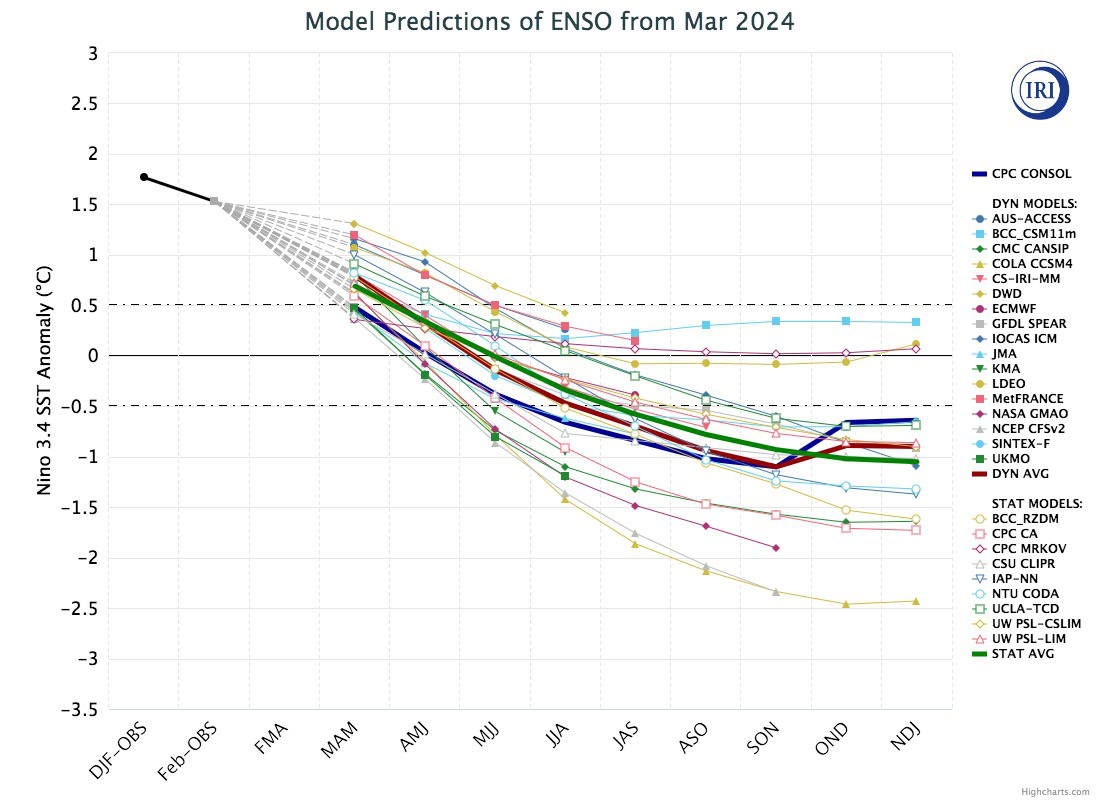

Currently, the ENSO sits within El Niño thresholds, meaning sea surface temperatures are warmer than average across central and eastern parts of the tropical Pacific. This El Niño event peaked at strong to very-strong thresholds late November last year, and has since been on the decline while greatly influencing snowfall in Japan and North America during the northern hemisphere winter.

El Niño is expected to weaken into neutral thresholds either later this month or during May. Normally, atmospheric responses lag behind changes in sea surface temperatures, but they seem to have jumped the gun and have been neutral or even La Niña-like of late, suggesting the sea and sky are taking a break and are doing their own thing for a while.

According to the BOM’s weather model, a strong pulse of tropical activity, known as the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO), is forecast to track across the Pacific over the next week or two. This may nudge the atmosphere back into El Niño mode for a while, potentially leading to a dry and settled lead-up to Opening Day, a prediction shared by the BOM and other seasonal models.

La Niña Lurking in the Deep

There’s good agreement among models that the tropical Pacific will continue cooling throughout the coming season, and a large body of cold water upwelling from below the surface adds credence to this. The consensus of models expects we’ll enter into a weak-moderate strength La Niña event sometime this season.

It’s not unusual for La Niña to follow on the heels of El Niño, especially after a strong El Niño like the one we’ve just had. This has happened roughly half the time in the past, and the change can be rapid with little time spent in neutral territory.

However, there is a big spread amongst individual models as to the extent tropical Pacific waters will cool off, leaving us with a lot of uncertainty at this point. The BOM’s own model keeps us in within neutral thresholds, as do other big players, such as the European and French models.

Say What? La Niña and a positive IOD, no way!

Historically, La Niña events were great for Aussie snow, as increased precipitation would often translate into deeper a snowpack. But over the last several decades, this relationship seems to have reversed, likely due to rising temperatures, so a bigger chunk of that extra precipitation now falls as rain.

Nowadays, La Niña events are less favourable than neutral ENSO conditions, but when coinciding with a negative phase of the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) – the Indian Ocean’s own version of the ENSO – we get the perfect blend of climate conditions for a heavy snowfall year.

The triple-dip La Niña years of 2020, 2021, and 2022, highlighted this relationship with the IOD beautifully. The IOD was neutral in 2020, weakly negative in 2021, then moderately negative in 2022, with overall snow conditions turning out to be rubbish, OK, and pretty-good, respectively.

This season, however, something extremely rare is expected to happen: a positive IOD and a La Niña at the same time! (cue ominous music).

Although forecasts for the IOD at this time of year are quite dodgy, there’s remarkably good agreement between models that a positive event is on the cards. In fact, the latest weekly index figure is above the positive threshold, so we could be in the throes of one already! (cue terrified scream).

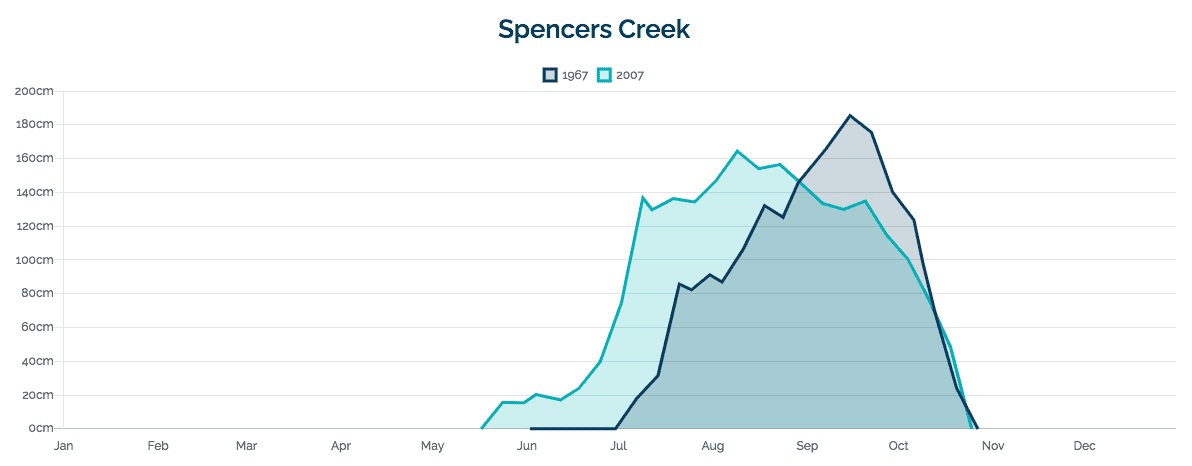

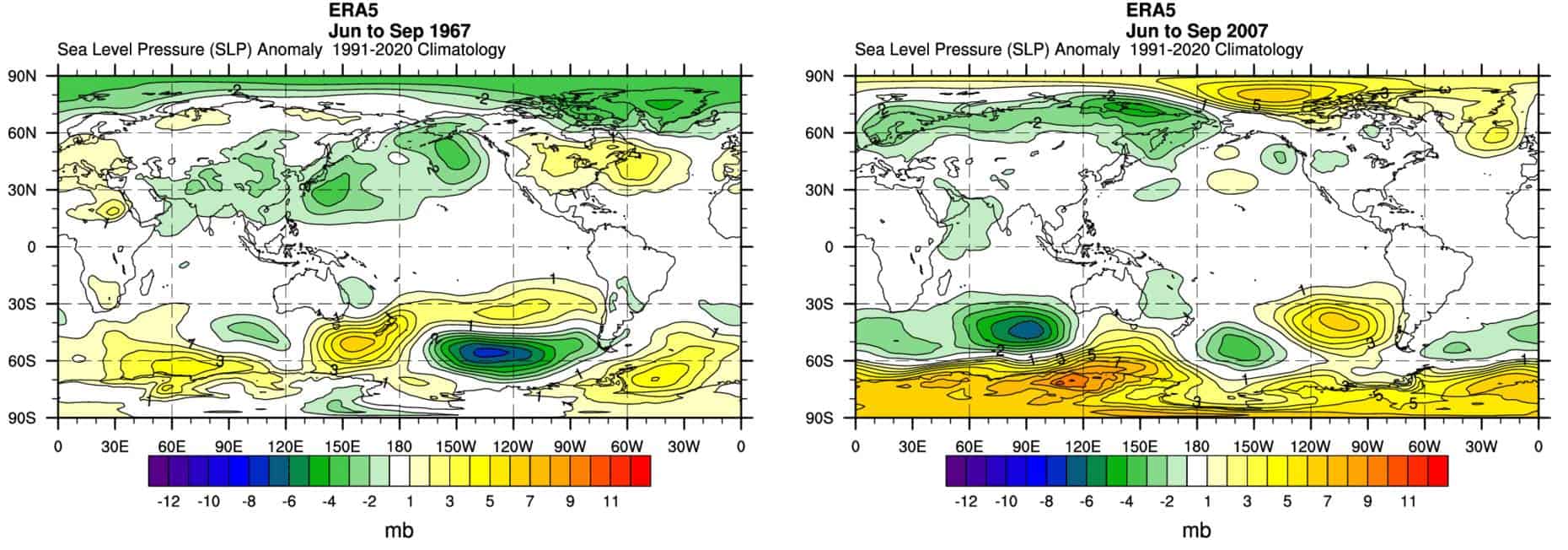

There are only two occasions in the books that a positive IOD and a La Niña have occurred together – in 2007, and way back in 1967. Both of those seasons weren’t great, but not too bad either, 2007 being the more consistent of the two, but only reached a max depth of 164.4cm at Spencer’s Creek, while 1967 was slow until good snowfall late in the season brought depths up to 185.4cm.

However, it is worth noting that both of these winters saw a few solid storms as illustrated below with a big increase in snow depth in mid-June (2007) and early July (1967). Whether storms will bring cold enough temperatures is impossible to say this far out. That largely depends on those wild regions south of Australia, an area seemingly ruled by chaos and randomness, which models struggle with beyond the two-week mark. We also need the Southern Annular Mode to swing into negative, which leads to cold westerly winds and cold fronts moving north across the Aussie Alps.

Positive IOD’s are usually bad news for Aussie snow, having a similar drying effect to El Niño’s. So it’s a curious situation we find ourselves in having two climate drivers – one wet, the other dry – opposing each other. Which one will win out? The relationship may be more nuanced than that, but we don’t exactly have a large dataset to go off.

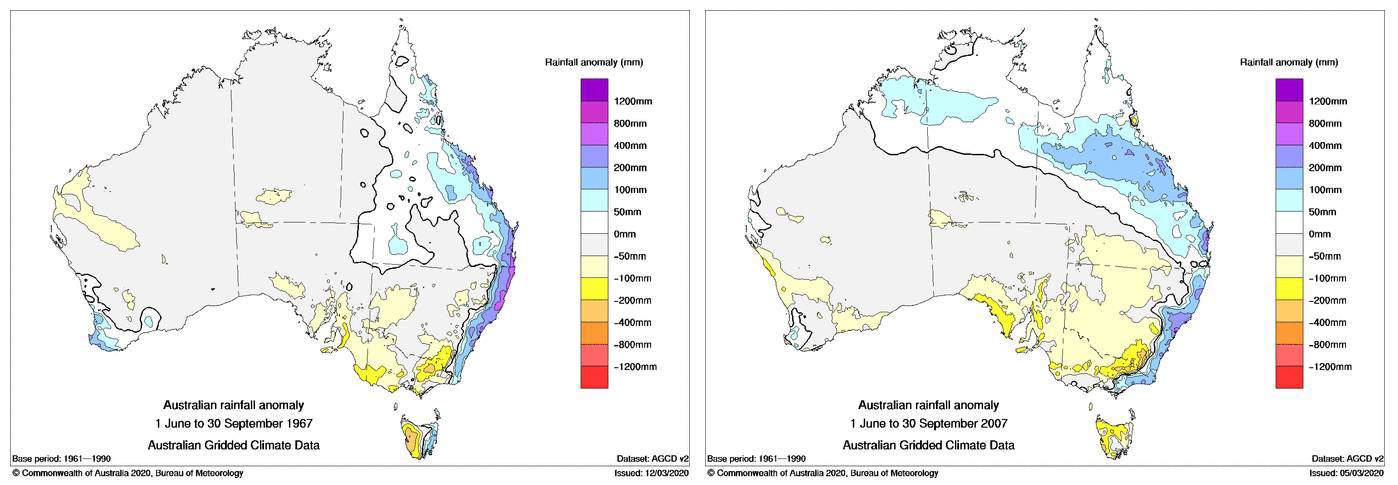

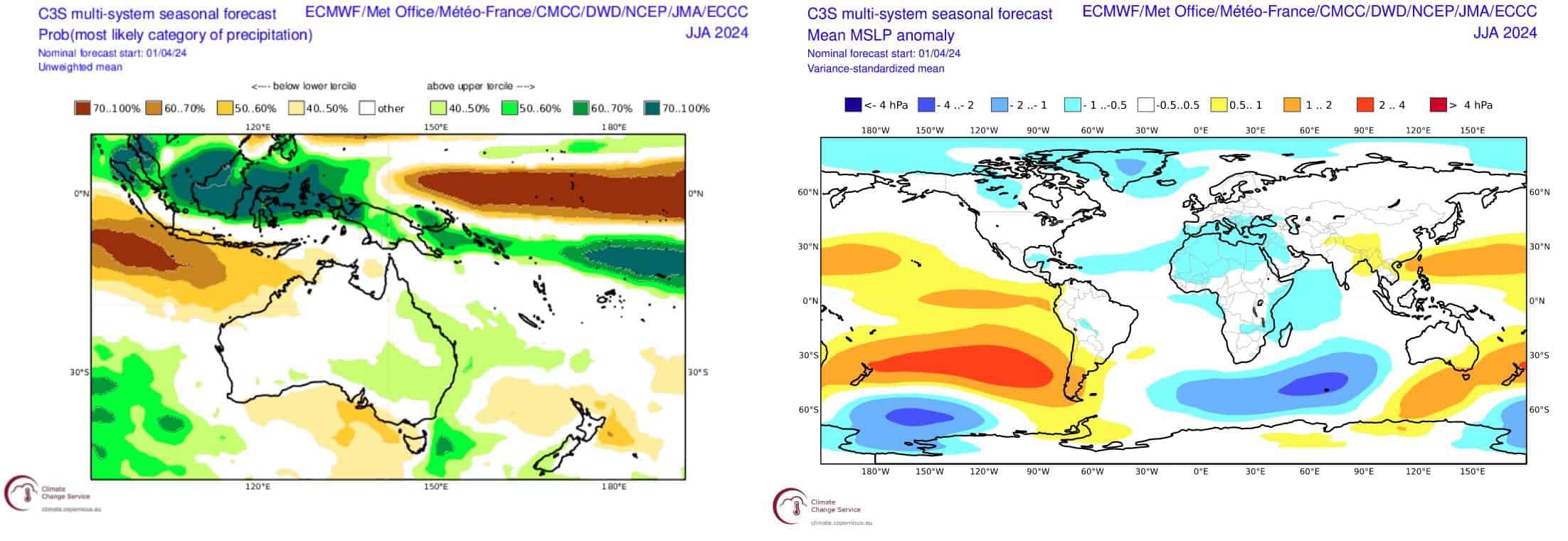

Overall, both the 2007 & 1967 seasons were dry in the Aussie Alps, and broader precipitation and pressure patterns around Australia were remarkably similar to each other. Most notable was that high pressure dominated to the south, while precipitation was high along Australia’s east coast with an apparent rain shadow elsewhere over New South Wales and Victoria, indicative of an anomalous easterly wind flow there.

Although the BOM and other models don’t specifically forecast the Aussie Alps to be dry this season, those same broader precipitation and pressure patterns are there. The images I’ve provided should hopefully illustrate this, and it’s a bit of a worrying sight.

Perhaps even more of a worrying sight are forecasts for temperatures. Any forecast that you can get a hold of will tell you that it’s going to be a warm one, with very high chances of winter being within the highest 20% of the historical range. This follows on from a year of global temperatures obliterating records left, right and centre in both air and sea.

These warmer temps will mostly affect lower elevations, making rain more likely and increasing snowmelt, and also shorten the season by pinching it at both ends. However, the possibility of clearer nights may allow artificial snowmaking to make up some of that shortfall.

Wrap up

There are a number of factors stacking up against a heavy snow season in the Aussie Alps this year, but one point I perhaps haven’t stressed enough is the level of uncertainty at this point in time. The Autumn months provide an awkward barrier to forecasting which gradually becomes more reliable when the monsoon transitions out of the southern hemisphere. There still remains a fair chance that both the ENSO and IOD will remain in a neutral state throughout the season, which on paper would make things look a lot better. I will have a better idea on that when I update the season outlook next month.

And remember, here we’re talking about averages over the length of a season. Big snowstorms can and will happen regardless of the state of climate drivers, which actually only account for perhaps a quarter of snowfall variation – the rest is left up to Mother Nature.

As in any season, it’s often about timing, and the best way to time it right is to keep a handle on weather forecasts, which you can do right here on Mountain Watch with top-of-the-line model data, and weekly forecasts by yours truly starting early June.

That’s it from me folks. If you’ve got a different theory on what’s going to happen this winter, or just want to provide feedback, then please hit me up on Facebook and hit the follow button while you’re at it.

The Grasshopper