Grasshopper’s 2024 Australian Snow Season Outlook – June Update

Mountainwatch | The Grasshopper

There’s been moderate amounts of snowfall across southeast Australia in the last week or so, with the best falls favouring the NSW ski fields. Ski fields at higher elevations in Vic also picked up some snow, but areas at lower elevations have had more marginal snow cover with rain dominating. Cool temperatures thanks to southerly winds over the last week – plus and a dry airmass with little rain – have been good for snow making in most areas, too.

There’s some top up snow expected Thursday and Friday this week – higher elevations will see more snow, but there looks to be at least of couple of centimetres in it. Next week, the last of June, has medium range models starting to suggest low pressure and frontal systems in the Great Australian Bight. As these try to move east across southeast Australia they might run into high pressure in the Tasman Sea. This set up can lead to northwest wind flow and warmer temperatures. Lower elevations are at the risk of seeing some rain, but higher elevations could pick up some snow. Keep an eye on my forecasts (Monday, Wednesday, Friday) to see how expectations evolve.

Now, what about the outlook for coming couple of months – July and August – and what can updated model guidance tell us and what are the main climate drivers up to?

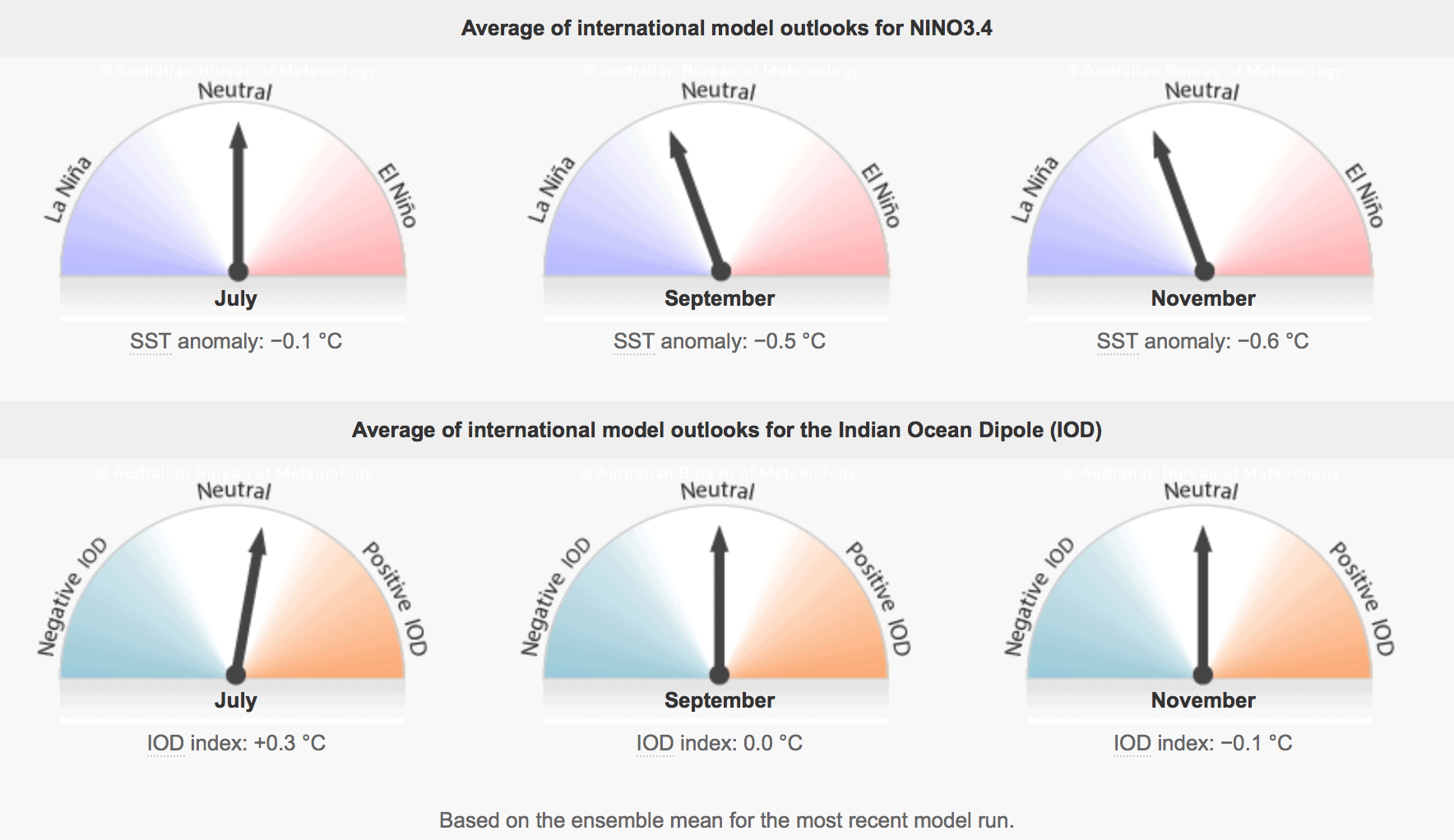

Firstly, the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) which looks at large scale changes in the atmosphere and ocean to the northwest of Australia – in the Indian Ocean Basin. The IOD is forecast to move into a positive phase in the coming weeks. Positive IOD is often characterised by warmer temperatures, but also drier conditions. This isn’t great news for the snow season, but there is a silver lining as drier airmasses can support snow making. Additionally, modelling is hinting at the possibility of the event being short lived and weaker than in my earlier outlooks, so impacts might be less pronounced.

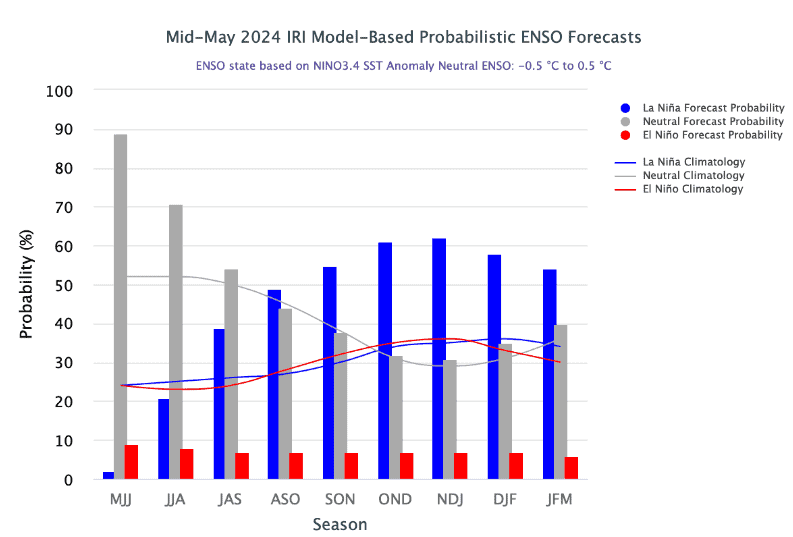

The other climate driver of note is the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO). This driver looks at the Pacific Ocean Basin and describes large scale changes in the ocean and atmospheric patterns in that region. Recent modelling has been forecasting a La Nina event to develop in the next couple of months. However, the latest update favours a delayed onset of La Nina – possibly during August, but more likely during spring.

La Nina can be a bit of a mixed bag for the snow season; while it brings increased rainfall to eastern Australia during winter, this doesn’t always eventuate in better snowfall. During recent decades, La Nina has often been associated with increased rainfall, and has at times washed away the snowbase. Historically, ENSO neutral years have had more consistent good snow depths than either El Niño or La Niña years.

For the winter months, the latest forecasts are leaning more towards an ENSO neutral phase. This means ENSO isn’t exerting a strong pull on the Australian climate; it’s not giving us a steer in terms of above or below average rainfall or temperature.

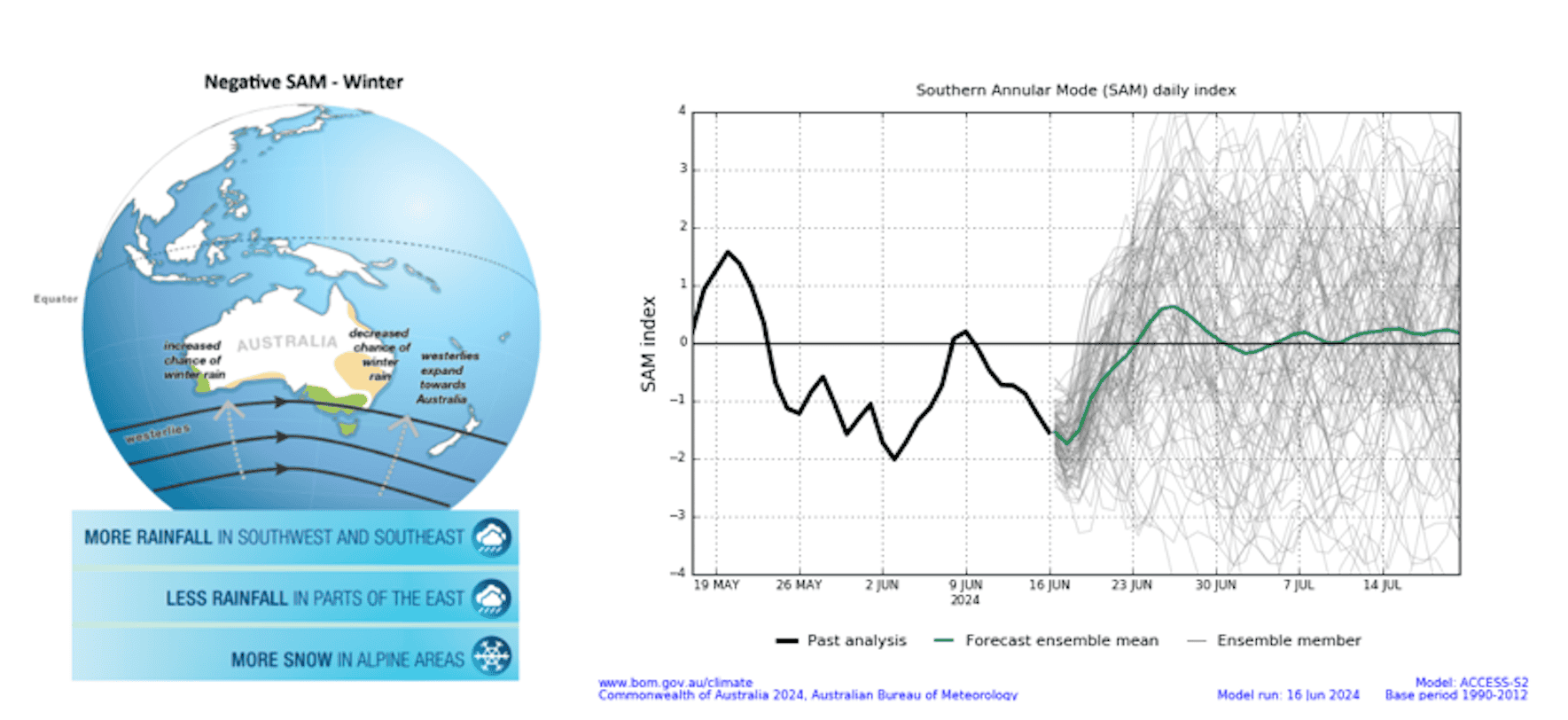

Short term climate drivers will also play a part in weather outcomes. One such climate driver is the Southern Annular Mode (SAM) which we spoke about last time. There’s a belt of cold blustery westerly winds across the southern hemisphere; the SAM describes the northward or southward shift of this belt of increased winds relative to its usual position. When these winds come closer to southeast Aus they can bring cold weather and snow.

Right image: A forecast for the SAM for the next couple of weeks. The green line shows the average of the different members of the ensemble forecast (grey lines). Note these ensemble members vary widely by the time we get passed about the 10-12-day time horizon, which shows that this parameter gets more difficult to forecast the further we look into the future.

Source: Bureau of Meteorology

Here’s the rub: the SAM is difficult to forecast more than a couple of weeks in advance. This means that the forecast for the next month or two could change at short notice depending on how the SAM plays out.

What’s the upshot? While the large-scale climate drivers like IOD and ENSO aren’t obviously favourably for snow this winter, natural variability in the short-term weather, plus other factors such as the SAM, means that we still “have it all to play for” this season. As we all know the best way to do that is to keep a handle on short-term weather forecasts, which you can do right here on Mountainwatch with top-of-the-line model data and my daily forecasts to catch the windows with the best conditions.

That’s it from me folks. If you’ve got a different theory on what’s going to happen this winter, or just want to provide feedback, then please hit me up on Facebook and hit the follow button while you’re at it.