2018-2019 North American Snow Season November Outlook – The Grasshopper

Patiently waiting with open arms for opening day. Photo: Mitch Winton, Whistler Blackcomb

A good start, but models suggest El Nino is alive and kicking

Mountainwatch | The Grasshopper

At a time of year when 46 million turkeys will be put to the sword and served up on American tables, we’re not only salivating at the thought of tucking into a Thanksgiving feast, we’re also drooling about tucking into some raw organic North American snow. When I say North American snow, I’m referring to mountains on the western side of the continent, that being the vast Rocky Mountains, the Coast Mountains of Canada, and the Cascade Range and Sierra Nevada of USA.

So far, the Rockies have been off to a great start with recent snowfalls allowing a lot of resorts to open a little earlier than planned. Closer to the Pacific Coast however, the Cascade Range and Sierra Nevada are looking rather bare, with only a handful of main trails open thanks to snow machines pumping out the non-organic variety. That won’t be the case for too long though, because a storm should roll in from the west this Wednesday, followed by a more vigorous and colder system during Thanksgiving on Thursday. Westerly winds will pump heavy snowfalls onto the Coast Mountains, Cascades and Sierra Nevada, with lesser but still generous snowfalls over the Rockies. We may even see a juicy low spin up over the Great Plains during Saturday, pushing cold air further south to ensure all of the Rockies get a second serving. When the feast is all over we could expect around 50-75cms to pile up along the Pacific Crest and about half that to fall elsewhere. For us southern hemispherians, that’s one heck of a way to kick off a season. Has the offering of all those turkeys pleased the snow gods? Now that we’ve had our fill, let’s get onto the real reason we came here – the snow season outlook.

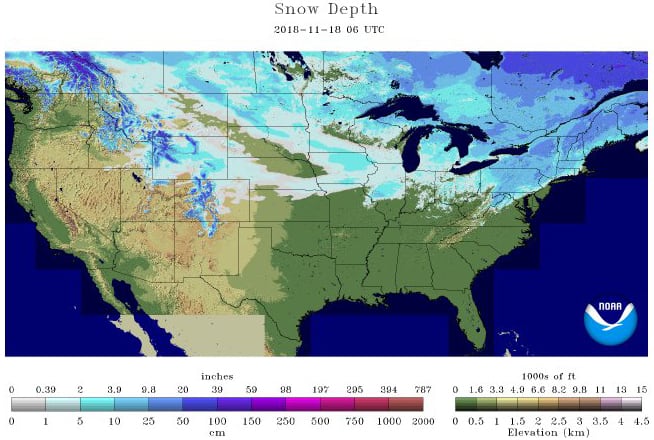

Current snow depths across North America showing there’s already snow to be had at resorts in the Rockies as well as the Coast Mountains of Canada. The Cascades and Sierra Nevada haven’t come to the party yet. Source: NOAA

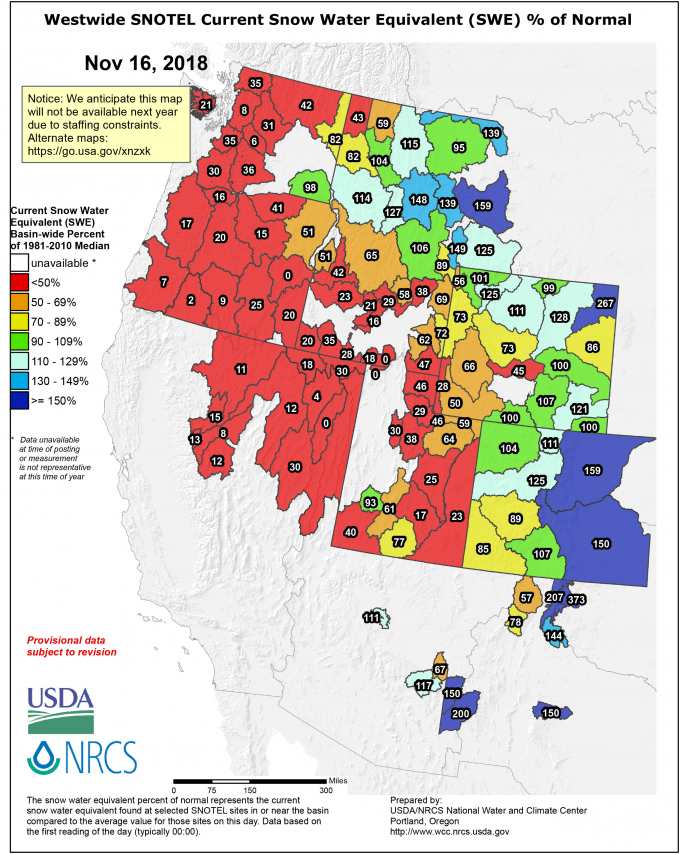

This is how the current snowpack is stacking up against climatological norms. The Rockies are off to a flying start with most areas ticking up average-or-above snowpack for this time of year. West of the Rockies is looking red hot and bare, but that’s about to change. Sorry Canada, I couldn’t find a sexy image like this for your neck of the woods, but the trend is similar. Source: National Water and Climate Centre.

El Nino nullified… or is it?

The El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is still hanging on to its neutral phase, but El Nino is knocking on the door and is expected to be established this side of New Years. There’s good agreement between climate models that a weak to moderate El Nino will last through the snow season.

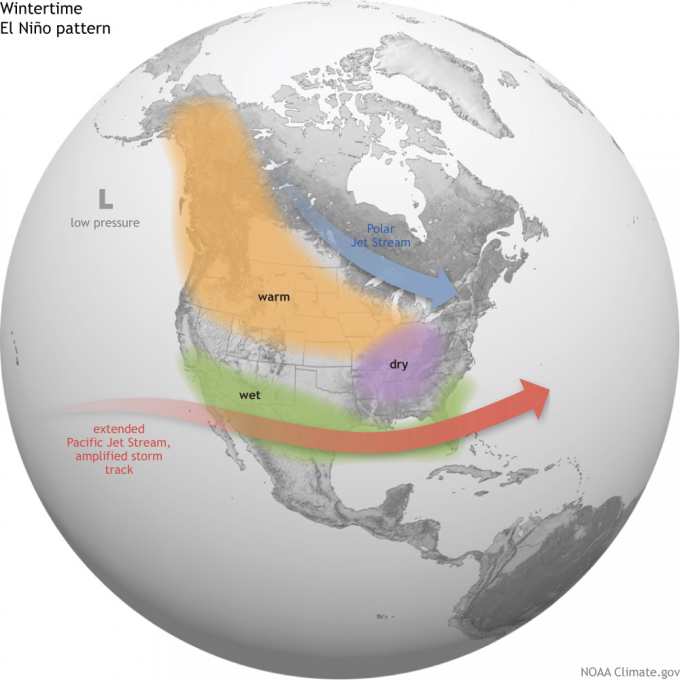

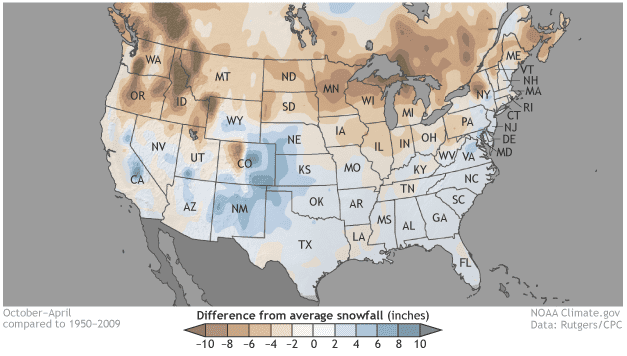

The two images below sum up the typical impacts an El Nino has on North America. El Nino has a tendency to shift the storm track further south, meaning that the southern states of America are cooler and receive more precipitation, equating to more snow for the Sierra Nevada and Mountains in Arizona and New Mexico. The outcome for everywhere else is a warmer, drier and less snowy vista. These are statistical findings of course, but in reality, year-to-year anomalies can look much different to this. The relationship is even weaker and more varied during weak or moderate El Nino phases.

The typical El Nino pattern over North America. Conditions tend to favour snow the further south you head, but worsen if you head north Source: NOAA

On average, snowfall anomalies for an El Nino event look like this. Things look good for the Sierra Nevada and the bottom half of the American Rockies, but a bit dismal elsewhere. Source: NOAA

To further douse the El Nino flame, something called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) is out of phase with the ENSO. I won’t go into too much detail about the PDO here, but basically it compares long-term sea surface temperatures between eastern and central areas of the North Pacific Ocean. When the PDO is out of sync the impacts of ENSO can be dampened or even vanish.With this in mind, it’s tempting to say that the looming ElNiño is likely to have little effect, but as you will see, climate models have a different story.

Climate models looking rather El Nino-ish

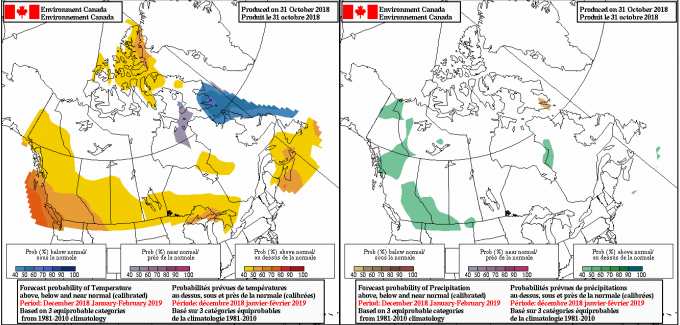

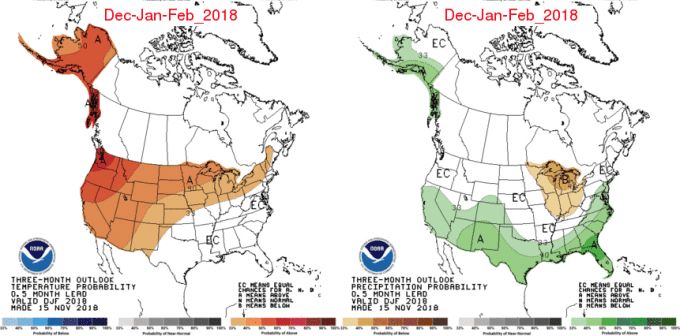

The seasonal outlooks issued by NOAA and the Meteorological Service of Canada (MSC) show that the western mountains of North America are likely to be warmer than average. This should lift the snowline a little and make rain more likely at low elevations. The outlooks also suggest we could see more precipitation fall over the Canadian Rockies as well as the southern half of America. At higher altitudes, where winter temperatures are permanently below zero, like at most ski resorts, we can chalk this up as above average snowfalls.

MSC climate outlook showing warm winter temps and the chance of above average precipitation/snowfall for the Canadian Rockies. Source: Meteorological Service of Canada

NOAAs outlook showing winter is likely to be warmer, as well as wetter/snowier in the south, which looks awfully similar to a typical El Nino scenario. Source: NOAA

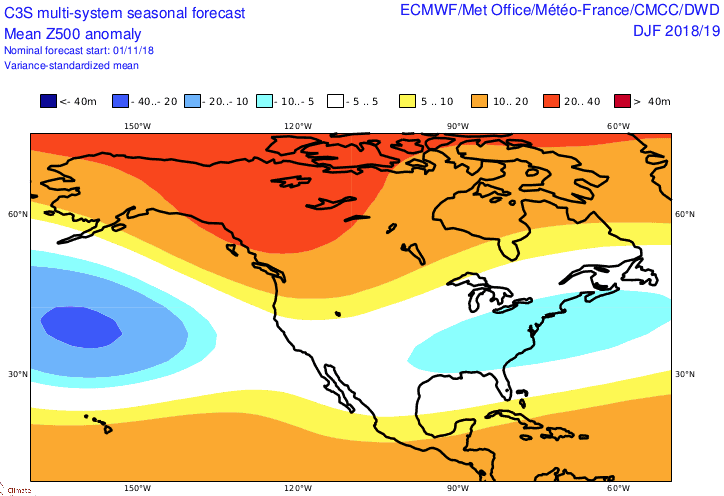

Other climate models generally agree with the outlooks above, although some, such as the ECMWF and UKMO, tend to smatter some dry areas near the Coast Mountains, Cascades and Rockies of the northern states of the US. Looking at the image below, I tend to agree with this notion. The image shows the mean anomaly of how high 500hPa pressures sit, which gives us a good indication of where most of the juicy storm action is likely to occur. We can expect plenty of storms to track over the southern half of the US, and less over the top half and Canada. This, as well as the outlooks from NOAA and MSC, looks remarkably like the typical El Nino setup. On closer inspection of NOAA’s climate model, we find the El Nino pattern springs up during the second half of the season, which is when the ENSO predominantly exerts its most influence. We also find that December may bring good fortunes to all, while January could be quite the opposite.

The super-duper C3S climate model giving us the mean anomaly of 500hPa geopotential heights for the winter months. We can expect plenty of storm action over the bottom half of America and less than average further north. Source: Copernicus Climate Change Service

Good, then slow, then good again down south.

After much research and analysis, and a lot of head scratching I have pieced together a picture that isn’t too bad. By the time we welcome in the New Year, our snowpack chart will be looking mostly blue and green; in other words, we should see average-or-above snowfalls for most mountain ranges during the rest of November and December.

We’ll have a slow down during January, then the Sierra Nevada and southern half of the American Rockies will pick up again as El Nino-like conditions kick in for February and March. Regardless of where this season will sit among history, North America really is the land of opportunity and there will no doubt be more than enough snow to have a cracking good time. So, gobble up that turkey and head on over for a genuine snoedown (a hoedown in the snow), yee-haw!

I’ll update this outlook in another month or so while the snow is piling up. I’ll be issuing weekly forecasts for both Japan and North America this season starting in December, so make sure you tune in. If you’ve got a different theory on what’s going to happen this winter, or just want to provide feedback,, then please hit me up on Facebook.