2022 Australian Snow Season Outlook – Turbulent Times Ahead

Mountainwatch | The Grasshopper

Here we go folks, the next round of the oft-turbulent Australian snow season kicks off in about six weeks time. I’ve tuned my antennae into the latest climate data, and it’s looking turbulent indeed. With high precipitation and a possible increase in cutoff lows on the cards, the season is on a knife-edge where cold temperatures will be the difference between powder turns and tussock turns.

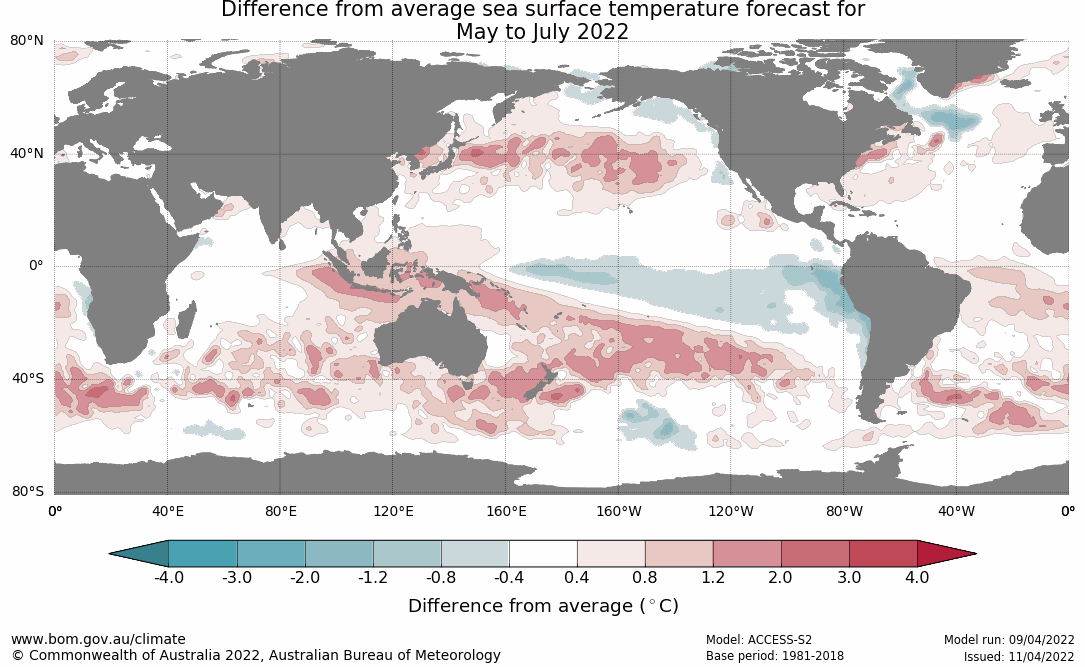

The big talking point in this outlook is the body of warm water surrounding the Maritime Continent north of Australia, stretching from the eastern Indian Ocean to the Western Pacific. Sea surface temperatures here are expected to get even warmer over the coming months, likely resulting in an abundant supply of moisture feeding into weather systems as they approach the Aussie Alps.

Models are accordingly gunning for the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) to dip into a negative phase in the next several weeks where it may remain for the rest of the season. This is typically a good thing for Aussie snow, and although IOD forecasts are often out-to-lunch at this time of year, there is great agreement between models.

The ENSO is currently at a weak La Nina level and is expected to continue weakening over the next month or two, dipping below the BOMs threshold for La Nina, but remaining above NOAA’s threshold (yes, they have different thresholds!). Weak La Nina or cool neutral, the tropical Pacific may provide extra moisture Down Under this season.

Will all this extra moisture fall as rain or snow?

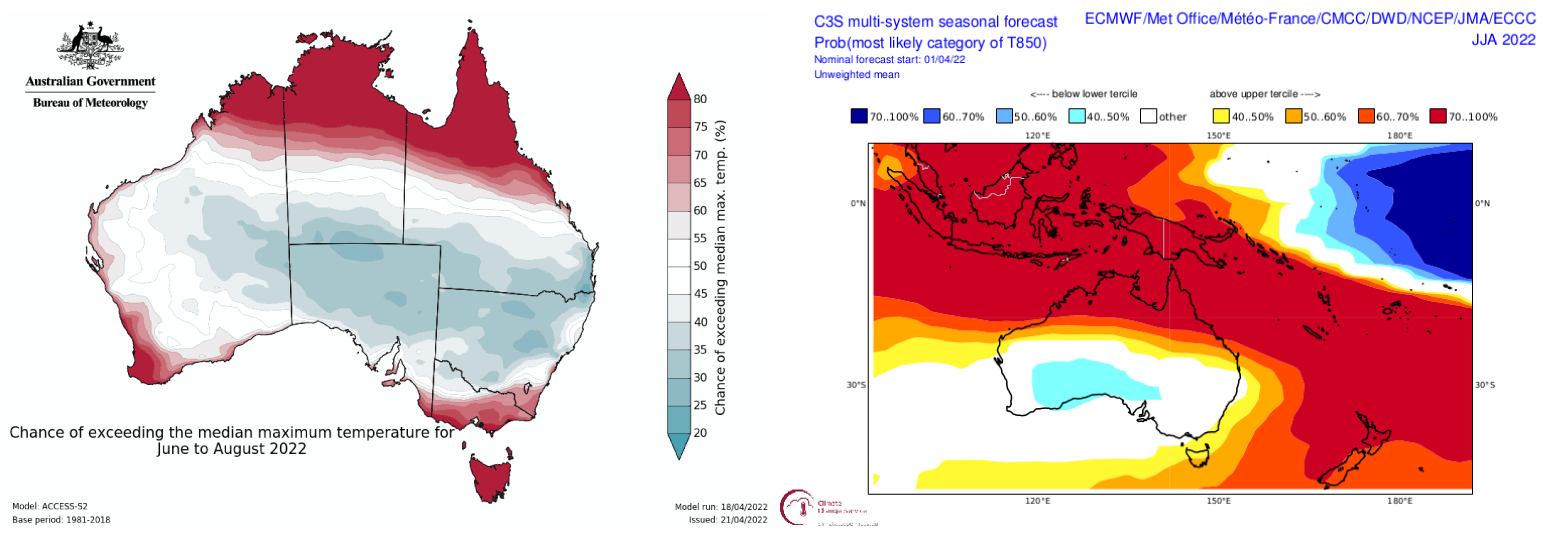

The key to answering this question is temperature, because as you’d expect there is a strong correlation between temperatures and Aussie snow. Mean winter maximum temperatures in particular have a big impact on peak snow depth and length of season; basically, the colder the better for Aussie snow.

So, it’s a bit of worry that the BOM expect mean maximum temps to be warmer this season. This isn’t necessarily reflected in the bulk of other climate models, however, the consensus of which expect mean temperatures will be about average.

There is also a danger in using seasonal temperature forecasts in this way as most Aussie Snow comes from infrequent, big storms events, which may have no sway on temperatures averaged out over a month or season. Seasonal temperatures are perhaps more indicative of the level of snow melt, rather than whether individual storms come bearing a relatively short-lived cold outbreak.

For example, despite being a warm winter overall last year, it turned out pretty OK in terms of snowfall, thanks to two big snow storms in July and another at the end of September, which Reggae raved about in his 2021 season wrap. Snow depths at Spencer’s creek reached 183.6cm and there was snow on the ground from start to finish.

Whether storms will bring cold enough temperatures is impossible for me to say this far out. That largely depends on those nether regions south of Australia, an area seemingly ruled by chaos and randomness, which models struggle with beyond the two-week mark.

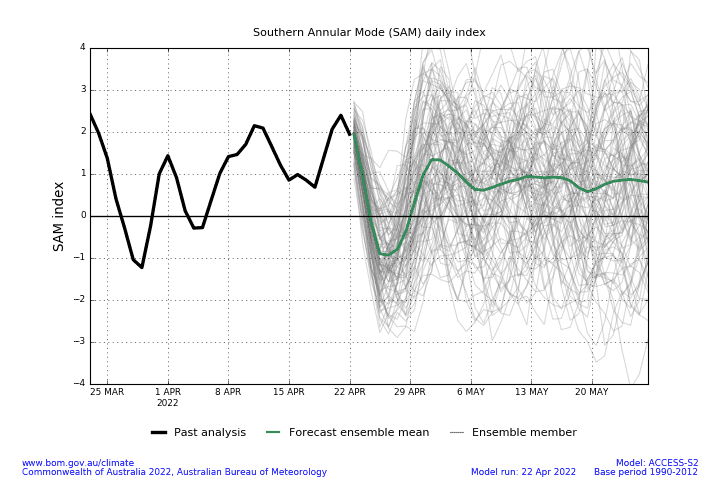

The Southern Annular Mode, or SAM for short, is an attempt to quantify what’s happening over the high latitudes by tracking the north-south position of the belt of strong westerly winds that persistently blow down there. Even here models go a bit coo coo at about the two-week mark, as shown in the graph below by all those manic scribbles.

The reason why I bring all this up is because seasonal models are more of a product of tropical forcings (e.g. ENSO, SAM) and long term climate trends (e.g. warming temps, expanding tropics, SAM becoming more positive), while misrepresenting the high latitudes due to its long-range unpredictability.

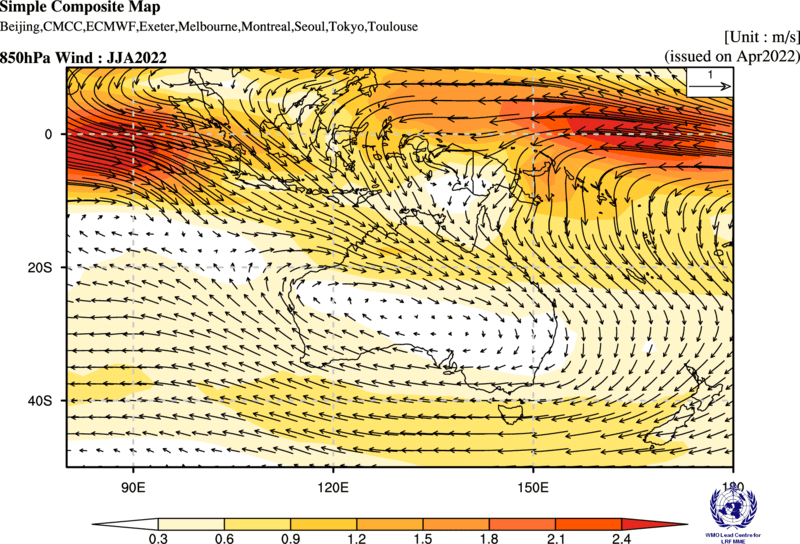

Take the image below for example, which shows wind anomalies at 850hPa (about 1500m) forecasted for the winter months. It shows an increase in wind flow down from that warm body of water north of Australia, and also an increase in easterly winds (or weaker westerly winds) along the south, leading to a terrifyingly wet, warm winter. But again, this how the tropics and long-term climate trends are playing their cards.

Wind anomalies at 850hPa forecasted for the winter months showing an increase in wind flow from the tropics and easterlies along and south of southern Australia. Source: WMO Lead Centre for LRFMME

The high latitudes may have a different say on the matter, however. An increase in storms from the south, likely indicated by negative values of SAM, could turn those easterlies right around, leading to a wet, cold winter and neck deep powder turns.

Outlook Wrap-up

Forcings from the tropics and long-term climate trends would dictate we’re in for a wet, warm winter, with an increase in easterly winds and cut-off lows wandering over southern and interior Australia.

Due to all the extra moisture, an increase in cloudiness is possible, making overnight temperatures warmer than average and potentially hindering artificial snowmaking.

Taken at face value, this doesn’t look good. However, a couple of good negative phases of SAM would turn those frowns upside down and possibly lead to a wet, cold winter, which is ideal for an above average season with limited snowmelt.

Additionally, the influence of the IOD and ENSO typically grows through the season, so we could have a game of two halves where the second half see’s more precipitation than the first. Also, an increase in easterly winds may see a lot more of that precipitation fall over resorts in New South Wales than in Victoria – a game of two halves split down the middle… a game of quarters, maybe?

One thing we can be grateful for at this point is that El Nino won’t rear is ugly head and a positive IOD is unlikely.

Well, that’s my two-bobs worth. If you’ve got a different theory on what’s going to happen this winter, or just want to provide feedback, then please hit me up on Facebookand hit the follow button while you’re at it.

Grasshopper.