Australian Seasonal Snow Outlook, Mid-Winter Update – El Nino Around The Corner

Mountainwatch | The Grasshopper

Before looking forward to the second half of the 2023 Australian snow season, it is worthwhile recapping what has eventuated so far, and if any of the trends seen are likely to continue.

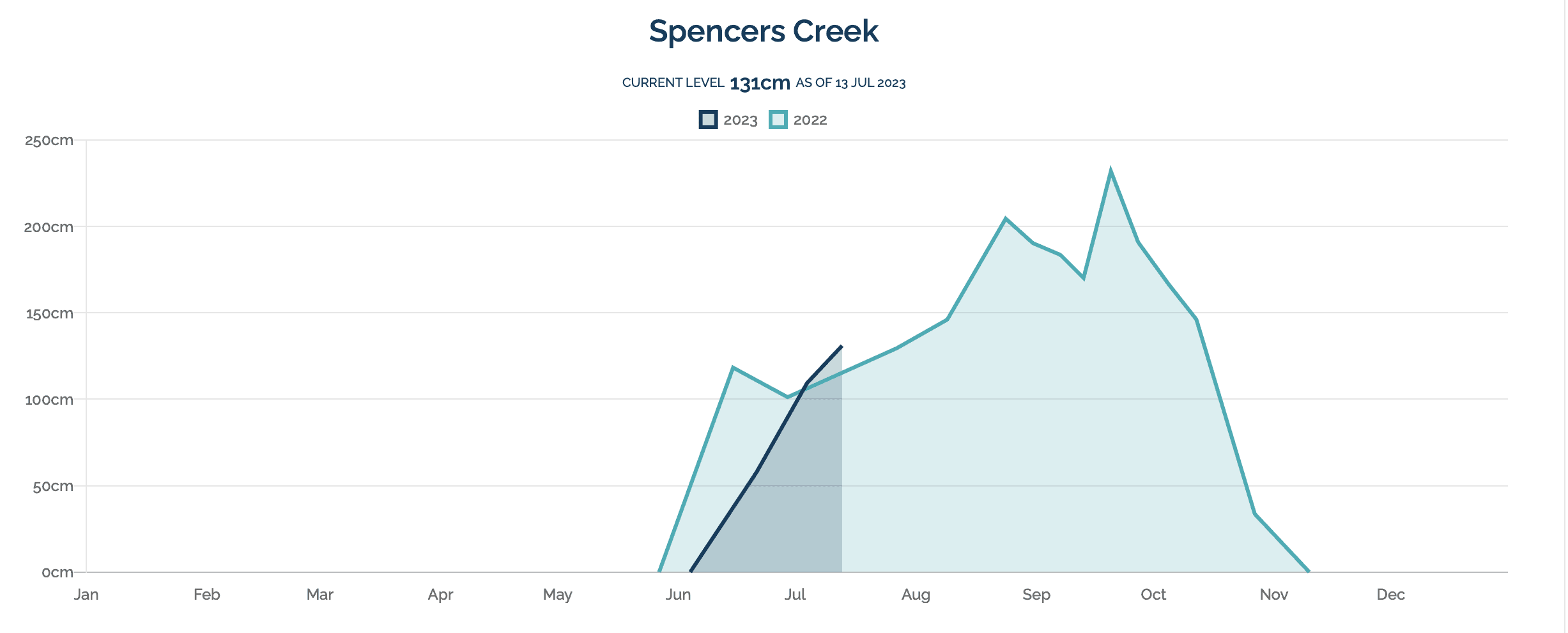

After an almost barren opening weekend in June, a strong series of cold fronts brought significant snowfalls to the Victorian and NSW resorts during the second half of June. By the 29th June, snow depths at Spencers Creek in NSW had exceeded the 100cm mark. Another significant front in early July boosted the snow depth to 130cm at Spencers Creek, while Falls Creek and Hotham exceeded 80cm. These depths are similar to those seen at the same time last year.

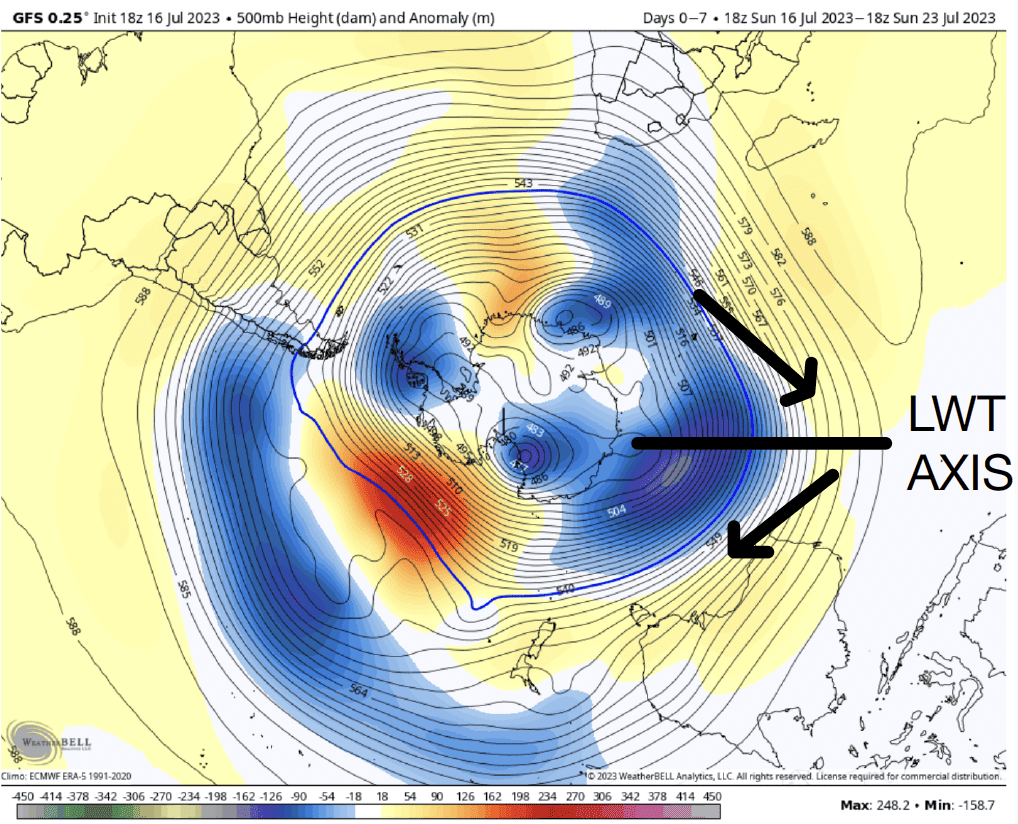

Most of the snow bearing cold fronts so far in 2023 have amplified northwards over Western Australia (due to the position of a near-stationary long wave trough in that region), before weakening and slipping southeastwards on their approach to the mainland ski resorts (Figure 2.)

This pattern has had a limiting impact on snowfalls (particularly for Mount Baw Baw on the south side of the Dividing Range) and has also kept winds out of the northwest quadrant in recent weeks. These northwest winds have brought injections of milder air to the resorts through the first half of July, along with jacket-soaking drizzle and reduced visibility. Daytime maximum temperatures this July have been more than 1℃ above the monthly average at the NSW and Victorian resorts, and more than 2℃ above for overnight minimums (although it has still been cold enough for snowmaking most nights).

Looking Ahead

In good news, the long wave trough pattern looks like changing during the second half of July, allowing cold fronts to remain a little stronger as they approach the southeastern states. With this shift, we should also see the recent prevailing northwest airflow switch towards the southwest more frequently, bringing more typical cold winter conditions to the Victorian and NSW ski resorts for the remainder of July. This should help with overnight snowmaking activities, and any natural precipitation that does fall is more likely to be snow than rain. Another 10-30cm of natural snow is the most likely outcome for the remainder of July, although there is the potential for an upgrade to this.

For August and September, we turn our eyes to longer term climate drivers for Australia, such as El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO), and the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD).

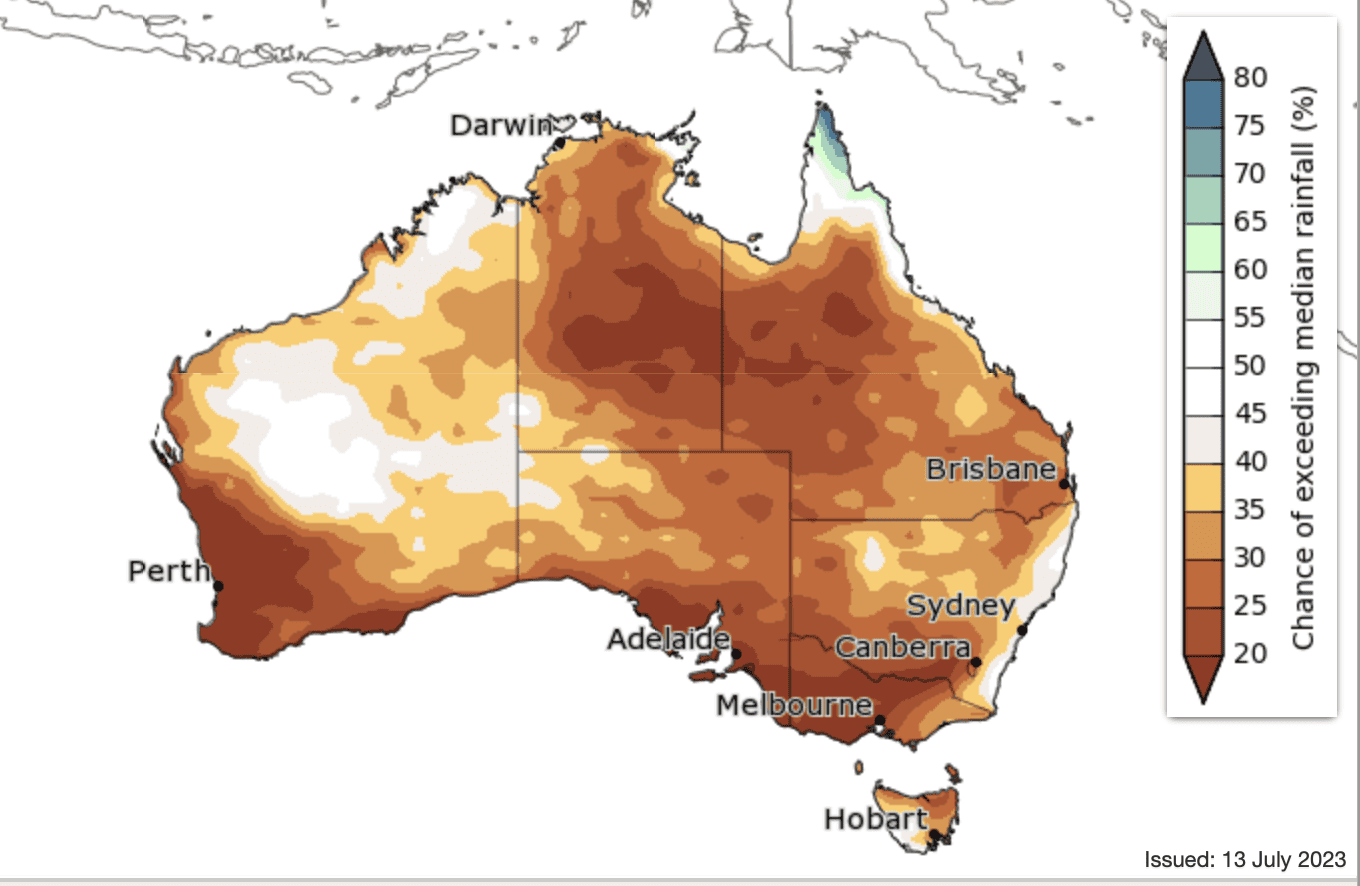

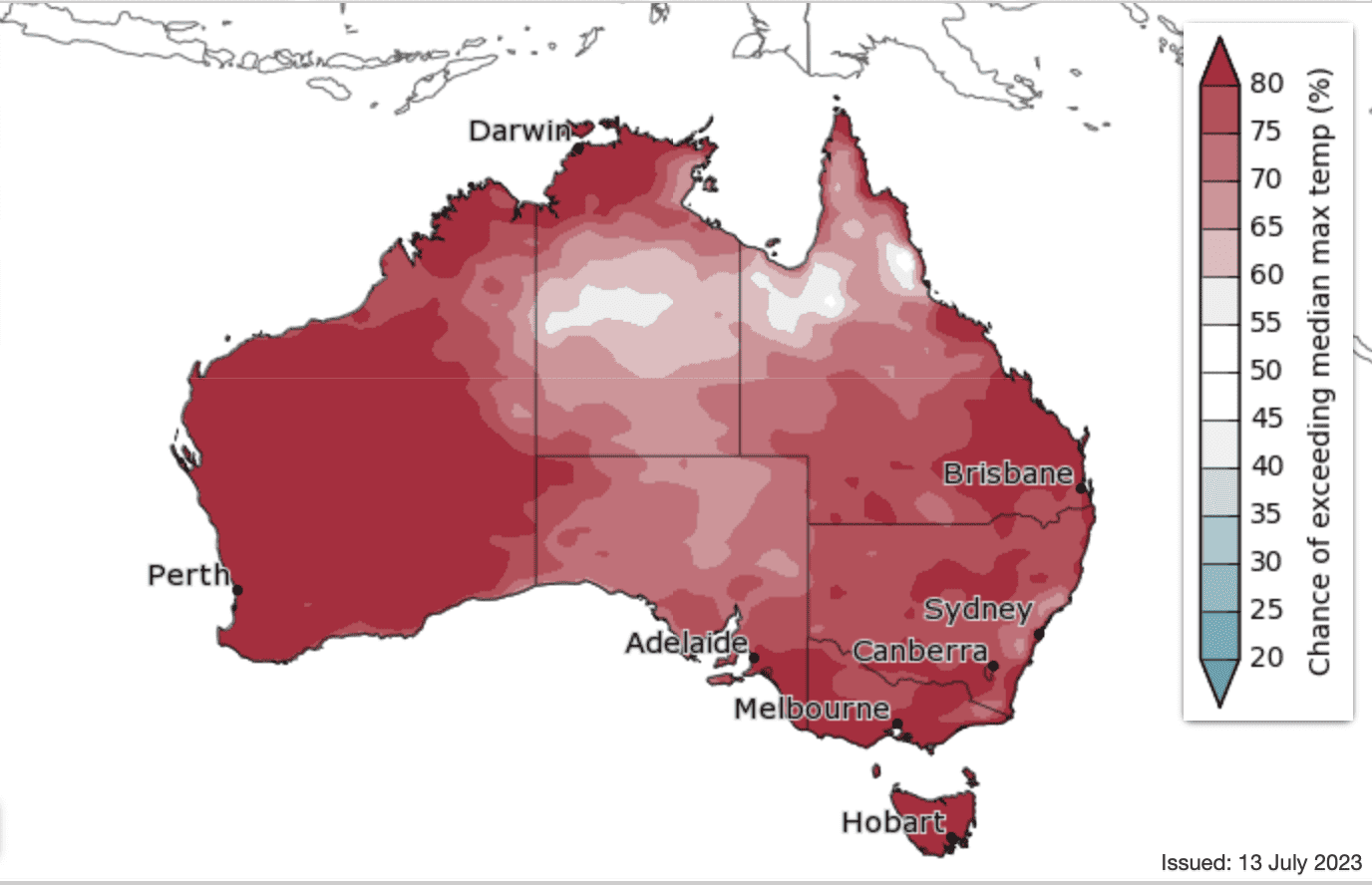

An El Nino event is likely to become established over the Pacific Ocean during August and September, as the atmosphere starts to respond to exceptionally warm sea surface temperature anomalies near the equator. Many international weather agencies (i.e., NOAA and JMA) have already declared that El Nino is with us, but the Australian Bureau of Meteorology is waiting for atmospheric indicators (like the Southern Oscillation Index and trade wind anomalies) to respond before making it official. Once they do, the typical late winter and spring impacts of El Nino for mainland ski resorts are; reduced precipitation (Figure 3), colder than average nights, warmer than average days (Figure 4). That being said, one or two large frontal systems during August and September could still deliver a boost to the base and some epic days, it’s just that the odds are weighted approximately 70/30 against there being above average precipitation. The other risk with El Nino is a rapid warming of the Australian continent into spring, which may cause an earlier than usual melt of the snow base.

That being said, one or two large frontal systems during August and September could still deliver a boost to the base and some epic days, it’s just that the odds are weighted approximately 70/30 against there being above average precipitation. The other risk with El Nino is a rapid warming of the Australian continent into spring, which may cause an earlier than usual melt of the snow base.

Figure 4. The % chance of exceeding median max temperature in September. Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology.

The other large-scale climate driver that can have a negative impact on late season precipitation for the ski resorts in NSW and Victoria is the Positive phase of the IOD. There were expectations at the start of the season that this unfavourable climate driver would be with us by now, but thankfully sea surface temperature anomalies across the Indian Ocean have remained at near neutral values. It is now unlikely that a Positive IOD event will become established in August, and probably September at the earliest, which gives a glimmer of hope that cold fronts will still pick up reasonable levels of moisture from the Indian Ocean in the coming month or two.

So, in summary, El Nino is probably going to take hold through August and September. This will limit natural snowfalls to a degree, and probably bring an early onset of warm days during September. Thankfully this situation doesn’t look like being compounded by a Positive IOD event, which might only get going towards the end of the season.

Short term synoptic patterns are going to play a more significant role in the near term, and it’s promising to see a change in the southern hemisphere long wave pattern unfolding over coming weeks, which may allow a few stronger cold fronts to pass through from late July into August. Southeastern Australia usually experiences at least one strong cold front during spring, so not all hope is lost, even if global scale climate drivers are not in our favour.

That’s it from me folks. If you’ve got a different theory on what’s going to happen this winter, or just want to provide feedback, then please hit me up on Facebook and hit the follow button while you’re at it. Remember, the key to scoring in the Aussie Alps is often about timing, and the best way to time it right is to keep a handle on weather forecasts, which you can do right here on Mountainwatch with top-of-the-line model data and my very own super-duper forecasts.