2018-2019 Japan November Snow Outlook – The Grasshopper

AVERAGE FALLS ON HOKKAIDO, BIT LESS THAN AVERAGE ON HONSHU

Mountainwatch | The Grasshopper

A quick scan of the webcams in Japan’s ski resorts today show idyllic grassy mountain pastures dotted with chair lifts, standing like sentinels waiting for the impending snowfalls.

That’s one thing we can count on in this part of the world – snow, and lots of it. The first few flakes will already be falling on upper slopes during the next day or so, and we can expect a nice wee taster of 5-15cm to low levels on Hokkaido and northern Honshu this Friday night and into Saturday. Tuesday and Wednesday next week look promising too with 5-10cm possibly falling on most resorts.

As I was saying, Japan is one of the snowiest places on the planet and its snow is of the finest, fluffiest quality. Between roughly 4m to 15m of snow usually falls every winter on 500 or so Japanese ski resorts. When we’re talking such crazy figures, even a bad winter here will blow your mind. Nonetheless, snowfalls amounts do vary a lot from season to season; about 15m fell in Niseko during the 2012/2013 season, whereas just under 7m fell during the 2016/2017 season. So let’s sit down and have a wee chitchat about how this season is stacking up.

Those grassy pastures will soon look like this and you too can get neck deep like KC Deane did in January 2018. Photo: Grant Gunderson

CLIMATE DRIVERS NOT GIVING TOO MUCH AWAY

First, let’s start with a little revision, shall we? The Japow Machine, the mechanism by which Japan receives so much of its light fluffy snow, basically works like this: freezing arctic air is pushed off Siberia and over the relatively warm Sea of Japan where it picks up moisture and becomes unstable. This air mass squashes up against Japan’s mountains, the highest of which stick above 3000m altitude, and is lifted up and forced to dump its moisture in the form of snow. This all happens at freezing temperatures that are perfect for making stellar dendrites, or rather the Shiba Inu of snowflakes – the fluffiest and most adorable of all Japanese dog breeds. These Shiba Inu snowflakes (that’s what I’m calling them from now on) are formed in the dendritic zone, which is roughly between -10°C and -20°C, which is just as well because any warmer or cooler and we would be more likely to have column shaped snowflakes; the Japanese Chin version of snowflakes – the least attractive Japanese dog breed (but still adorable).

Perfection! More Shiba Inu snowflakes than you can dream of. Photo: Zach Paley/Niseko Photography & Guiding

Japan also cops a fair bit of snow from lows that pop up in the Yellow or East China Seas, which can drop around the bottom of Japan and then approach from the Pacific side. These tend to be warmer in nature and can bring rain to elevations higher than we would like. However, sometimes they bring a bottle of saké to the Japow party by spilling a tonne of moisture over onto the Sea of Japan side, which is then undercut by the freezing northwesterlies off Siberia. This is called “over running” and is exactly the same scenario that brings big snowfalls to the eastern side of New Zealand’s Southern Alps, except here it is a Matsuri, a Japanese festival, rather than a Kiwi keg party.

The Japow Machine is part of the general flow in this part of the world called the East Asia Winter Monsoon (EAWM). A strong EAWM ensures Japan will see plenty of snow, and it is positively correlated to autumn snow cover over northern Asia. The good news is that northern Asia had slightly above average snow cover during October. The bad news is that we’re likely to have a weak to moderate El Niño, which can weaken the EAWM and is often associated with lower than average snowfall on Honshu.

The EAWM’s relationship with the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is complicated however, and it usually requires something called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) to be in sync. I won’t go into too much detail about the PDO here, but basically it compares long-term sea surface temperatures between eastern and central areas of the North Pacific Ocean. Fortunately, the PDO is currently out of phase with the ENSO, so it’s likely the looming El Niño will have little effect. There are a bunch of other climate oscillations that have an influence on the EAWM, such as the Arctic Oscillation, but at present we’re not good at forecasting them beyond 10-14 days ahead. I will talk more about these climate oscillations later in the season, once we get into the thick of it.

The North Face athletes Hank Bilious and Fraser Mcdougal skiing the amazing powder that Myoko Kogen has to offer.

CLIMATE MODELS ON THE LIGHT SIDE

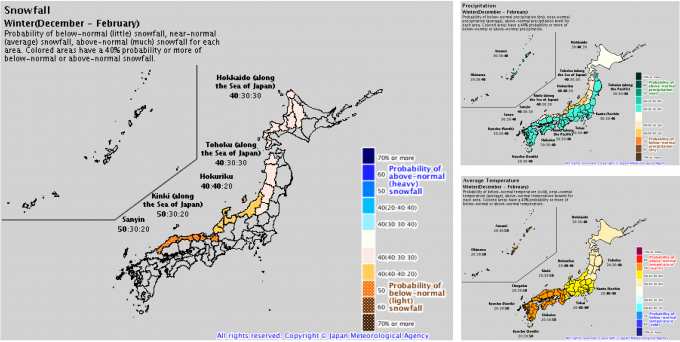

JMA’s winter outlook shows the scales slightly tip towards below average snowfalls the further south we head down the country. Source: JMA

In all their winter outlook charts, the good folks up at the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) have coloured the Sea of Japan side in yellow and orange hues. The general vibe from their forecast is that, although average snowfalls have a good chance of occurring, the further south we head along the archipelago, the more the scales tip towards below average snowfalls and away from above average.

JMA’s outlook for temperature and precipitation follows a similar trend where warmer and drier conditions are favoured on the Sea of Japan side of Honshu.

Interestingly, the Pacific side of Honshu, as well as Shikoku and Kyushu may be wetter and warmer than average, which is likely to be a response to warmer sea surface temperatures expected in the Yellow and East China Seas and nearby waters of the Pacific. It also suggests that we could see plenty of lows approach from these warmer climes, as well as a weakening of the EAWM (in other words, less of those juicy northwest winds off Siberia). This is backed up by pressure anomalies forecasted by NOAA’s climate model, which indicates a weaker Siberian High and Aleutian Low as well as lower pressures over the Yellow and East China Seas. Although JMA’s outlook leaves a little sour taste, it has hasn’t quite got me shaking in my ski boots.

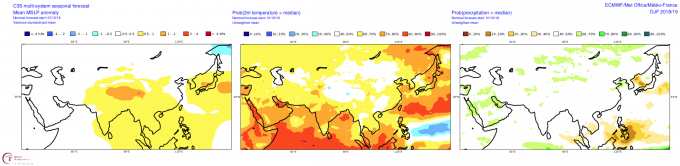

The C3S super-duper climate model forecast for winter pressure anomalies (left), 2m temperature probabilities (middle) and precipitation probabilities. If you squint, you can see Japan in the top right of each picture. The odds are stacked against above average snowfalls with high pressure, warm temps and dry spots. Source: Copernicus Climate Change Service

Other climate models, such as those run by the ECMWF and the UKMO, tell similar stories to the JMA. They’re all fairly consistent with warmer than average temperatures and hints of dry areas, but they differ from the JMA regarding wetter conditions on the Pacific side. They also lump high pressure over much of Japan, particularly over the southern end, indicating that we’ll see more settled weather than normal. This isn’t exactly a bad thing. As I alluded to earlier, a bad season in Japan will still see metres upon metres of snow fall, so more settled weather will just mean better conditions to shred in.

LESS SNOW, MORE SUNSHINE, STILL EPIC

After a quick glance at major climate drivers and their indexes, nothing stands out at me to say that this season will swing one way or the other. On the other hand, climate models and the outlook from JMA suggest that we’ll see below average snowfalls, particularly on Honshu. The overall vibe I’m getting is that we can expect average snowfalls on Hokkaido and 5-10% less on Honshu. Don’t let that put you off any ski trip to Honshu though, because you’ll be better placed to score some sunshine there. You can be rest assured that there will be plenty of Japow to float through, and any deficit in snow will most likely only be noticeable at either end of the season.

Hopefully I have whetted your appetite for a bit of Japow and provided some saké for you to mull over. I’ll update this outlook in another month or so while the snow is piling up. I’ll be issuing weekly forecasts for both Japan and North America this season starting in December, so make sure you tune in. If you’ve got a different theory on what’s going to happen this winter, or just want to provide feedback, then please hit me up on Facebook.

This Japan outlook is sponsored by the Japan travel specialists, Liquid Snow Tours. They have a range of great value ski packages available across Japan but availability is filling up fast. 7 night ski packages start from only $1128, enquire now for a free quote.

If you haven’t already, don’t forget to enter our competition with The North Face to win an all inclusive trip to Hakuba!