2018 Canada Snow Season Outlook – The Grasshopper

Early season snow storm at Whistler Blackcomb

Mountainwatch | The Grasshopper

Justin Trudeau, maple syrup, poutine, and absolutely stunning mountains. What’s not to love about Canada? If you’re thinking of heading away for some northern hemisphere snow this season, then let me give you the lowdown on one of my hopping favourite places, Canada.

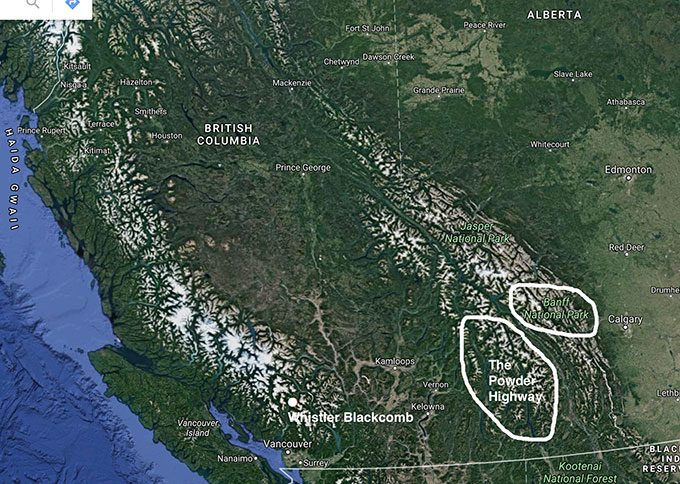

Canada’s mountains

The area of Canada most well known for skiing is British Columbia (B.C.), and the seaward mountains of British Columbia boast Canada’s most well known resort, Whistler Blackcomb. Easy access from Vancouver makes Whistler a popular local and international destination, and although amounts can vary a lot from year to year, proximity to that great big puddle of moisture known as the Pacific Ocean makes heavy snowfall a near certainty. In 2016 over 12m of the stuff landed there, and the base usually sits around the 1.5-2m mark.

Further inland the northern spine of the Rockies crosses the 49th parallel and becomes, in my humble hopper opinion, the jewel in Canada’s skiing crown. The western side of the Rockies, known as the Kootenay Rockies, is home to the aptly named Powder Highway. An 800 mile loop around inland B.C., the Powder Highway offers access to some of the greatest variety of skiing in the world, not to mention of course some of Canada’s best quality powder.

The eastern side of the Rockies come down in Alberta and it’s hard to find a better package than Banff National Park. A UNESCO world heritage site, Banff has jaw dropping views, world class resorts, hot springs, and powdery snow. Their biggest resort, Lake Louise, is already open, after a double hit of snow in the first week of November put almost 50cm on the ground in some places.

Over in eastern Canada clusters of smaller ski resorts can be found within driving distance of the main cities – Toronto, Montreal, and Quebec City. Whilst not as dramatic as their western cousins, they provide a variety of options from quaint to world class resort for those wishing to explore out east.

Snow quality

Being north of the 49th parallel brings one distinct advantage – proximity to cold arctic air, one of the key ingredients in the making of fluffy powder. British Columbia also lies on the edge of the Pacific Ocean, and it is this combination of moisture source and cold air that means the Canadian mountains receive some of the best powder getting around.

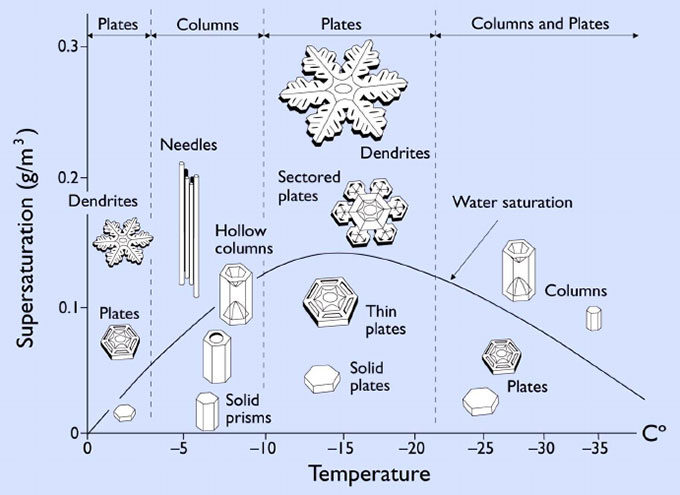

Storms blow in from the Pacific, and this moisture laden air is pushed up over the mountains causing it to cool and condense its water vapour into water droplets or ice particles in the air. The temperature at which this process happens and the temperature at the surface where it lands are what determines whether we get wet snow, dry powder, rain, freezing rain or graupel. To produce snowflakes, or “stellar dendrites” as they are known in the biz, we need this process to occur in what is called the dendritic zone, roughly -12°C to -18°C. If these then fall into cold dry air, such as comes down from the Arctic, they keep their dry fluffy snowflake qualities when they hit the ground, and we get fresh powder to play in.

In mountainous regions like British Columbia, the atmosphere above the mountains is as complex as the mountains themselves, and snow is formed and falls into a range of temperatures. In general, wetter, heavier snow is formed in the up slopes of the seaward ranges, where some of this condensation process occurs at warmer temperatures than the dendritic zone. Head further east and the powder gets fluffier as the moist air is more often condensing in the dendritic zone and the surface air is drier. Eventually the whole system is wrung dry and you are east of the mountains in the rain shadow.

Even along The Powder Highway we can find large variation in snowfall amounts and quality from mountain to mountain. For example, Revelstoke, which boasts North America’s largest vertical at just over 1700m, receives around 12 metres of snowfall per year. A mere 150kms further east along the Highway we find ourselves at Kicking Horse which receives only 7.5 metres per year, but by all accounts has some of the driest and fluffiest powder known to man and grasshopper.

Snowflake morphology diagram. It is sometimes called the Nakaya diagram after Ukichiro Nakaya, the physicist who first figured out how snow crystals grow in the 1930’s.

Seasonal Indicators

There are multiple meteorological indicators that can give us a steer in forecasting conditions weeks or months ahead. You can think of them like the background conditions for the atmosphere, and knowing them can give you a statistical indication of particular outcomes being more or less likely. It’s a bit like knowing that when the rugby pitch is wet the Wallabies are more likely to beat the Springboks (disclaimer, I don’t actually know the stats on that!). It doesn’t mean that they win every game on a wet pitch, but in the long run if you looked at all the games played on a wet pitch the Wallabies would have won more.

Problems arise when multiple indicators are pointing in differing or unclear directions making it hard to draw any meaningful conclusions. What if the rugby pitch is wet (Wallabies more likely to win) but they are playing in South Africa (Springboks more likely to win). And now what about if we consider the results of the last three games? And injuries? In many ways, forecasting the weather weeks ahead is a bit like picking rugby results weeks ahead. We can have all the ducks lined up in a row indicating the Wallabies should win a given match, but on the day it just might not go that way.

ENSO

Most of you will be familiar with the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) as a large scale weather driver that can impact snowfall over a season. ENSO is currently neutral, with about a 50/50 chance for it to stay like that, or develop into a weak La Niña over the northern hemisphere winter.

What does this mean for the Canadian ski season? Well given the close to neutral state, and the challenge these days of incorporating climate change into seasonal predictions, it doesn’t tell us a huge amount. But in the spirit of a background signal, we can liken it to the Wallabies being on the home pitch. As a single indicator, it is favourable news for the B.C mountains, as over the years La Niña’s have tended to mean an early snow base and above average amounts of snow. Given we‘ve already had the first snow storms that seems to be going to plan for now.

As we head through the season we will keep an antenna tuned to other sub-seasonal medium range indicators, such as the Arctic Oscillation (AO) and the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO). These can help us pick incoming powder dumps, and you can read a bit more detail about these in my USA outlook (link).

Resorts

I’ve mentioned a few resorts already. For experts travelling The Powder Highway looking to maximise boasting points don’t miss Kicking Horse Mountain Resort. With 60% of its runs black diamond or double black diamond, it’s not to be taken lightly. Nearby Revelstoke is more geared to intermediates wanting to end the day with really tired legs. 40% of its runs are rated intermediate and 40% black diamond, and it has North America’s largest vertical at over 1700m.

A couple of other standouts, for families or those after a more rounded experience – Panorama Resort does exactly what it says on the tin. North American Resort of the Year at the World Snow Awards 2016, you go there for sheer jaw dropping amazing views and a mix of terrain to suit beginners, intermediates and experts alike. Lake Louise is another premium resort, with a range of terrain to suit all abilities, and is one of only a handful in the world located in a UNESCO world heritage site. Don’t forget your camera.